Get Out of Your Comfort Zone

Christina Brown | Bachelor of Architecture 2020, Master of Science in Sustainable Design 2020

This work was presented at the Asian Conference on Sustainability, Energy, and the Environment (ACSEE 2020) and will be presented at the National Council of Science and the Environment Drawdown Conference 2021 - Research to Action: Science and Solutions for a Planet Under Pressure and at the International IAFOR Conference on Sustainability, Energy, and the Environment (IICSEE Hawaii2021) as a recipient of an IAFOR Scholarship.

Advisors:

[B.Arch 2019-2020] Marantha Dawkins (CMU), Herbert Dreiseitl (Dreiseitl Consulting), Vivian Loftness (CMU)

[MSSD 2020] Erica Cochran (CMU), Dana Cupkova (CMU), Vivian Loftness (CMU), Azadeh Omidfar Sawyer (CMU)

As global warming accelerates, buildings currently account for 39% of energy-related carbon dioxide emissions annually. Despite this fact, architecture is increasingly designed to be fully boxed in and internalized, requiring increased conditioning, which in turn further contributes to the greenhouse gas emissions warming up our planet. Technology has evolved where we can now disassociate ourselves from the natural environment and isolate our spaces completely. This has also created spaces where people begin to disassociate from their community, and live within boxes both physically and socially. Though current research addresses many environmental and human health concerns that arise from internalized architecture, it does not address the social disconnection nor is there any specific terminology and research that focus on externalizing programming as a strategy. To fill this gap, this synthesis establishes important terminology and research to support ‘externalization’, and explores the environmental and social impacts of externalizing programs through both design evaluation and morphology.

This synthesis first establish key terminology, literature review, case studies and research to highlight the importance and impacts of externalization both in terms of social and environmental connectivity. Then an externalization taxonomy is introduced to support designers in two ways – first as a design evaluation tool that can aid in evaluating architectural design through its environmental and social connectivity, and second as a design support for building morphology and evaluation that would better demonstrate how externalization can create integrated designs that provide layers of environmental, social, and health benefits while reducing the total building energy demands. This morphology process will be conducted on the Environmental Charter School in Garfield, with varying levels of externalization, to demonstrate the impact of externalization on architectural design while also showcasing how externalization could be integrated into architectural design practice. Lastly this synthesis will discuss the potential role of externalization in terms of the pandemic (COVID-19) and social inequity within architecture.

This synthesis will provide foundational research and frameworks in regards to building program externalization, and provide preliminary research and example of how to evaluate architecture based on externalization criteria and how to integrate it into architectural design. The synthesis provides the necessary groundwork to allow for externalization to be researched further, and provide architects and designers with convincing arguments to adopt this approach into their own design work.

The idea of “universal climate” or “la respiration exact” created by Le Corbusier was an idea that resonated with generations of modernists. At that time the application was challenging due to technological challenges, but as technology and science continue to develop, we have now successfully achieved our goal of hermetically sealed buildings due to the innovation in the air conditioning industry and the development of the psychometric chart (Willis Carrier) (amongst other advancements). However with this new found ability to produce artificial environments, we have also successfully disassociated ourselves from the natural environment by relying solely on mechanical conditioning even when we are equally able to open a window or a door. We now treat space as a simple box, internalizing all our design efforts inside the conditioned box, rather than considering what spaces could be outside or externalized to outdoor environments.

In addition to disassociating people from the natural environment, this conventional approach also creates spaces where people disconnect themselves from their communities. The social vibrancy of a community isn’t embedded into the architectural design, so a corridor is simply for walking (rather than meeting neighbors and chatting), a lobby is purely to enter the building (rather than serving as a community gathering space for all its tenants), and the rooftop is just for mechanical systems (rather than acting as an urban farming space for its community). The vibrancy of hearing children playing, people chatting, and the birds chirping is all taken away as we build glass walls around ourselves on all sides. We have internalized ourselves away from our local communities, resulting in vacant and disconnected neighborhoods.

Photos taken by: Vivian Loftness (far left), unknown (center left),

Alexey Ds (center right),

Liam Frederick (far right)

Photos taken by: Vivian Loftness (far left), unknown (center left),

Alexey Ds (center right),

Liam Frederick (far right)“Why aren’t we embracing connections to nature and community?”

I began to question why this was our status quo, and what was the reasoning behind why we designed in such a manner after studying abroad in Singapore. Throughout my study abroad experience (as shown below), I was able to experience externalized architectural spaces in various countries and climates that all demonstrated a richer environmental connectivity and social vibrancy that wasn’t present in how we currently designed architecture. This made me begin to inquire into the idea of “externalization”.

Photos taken by me

Photos taken by me“What does ‘externalization’ really mean? How would ‘externalization’ be evaluated?”

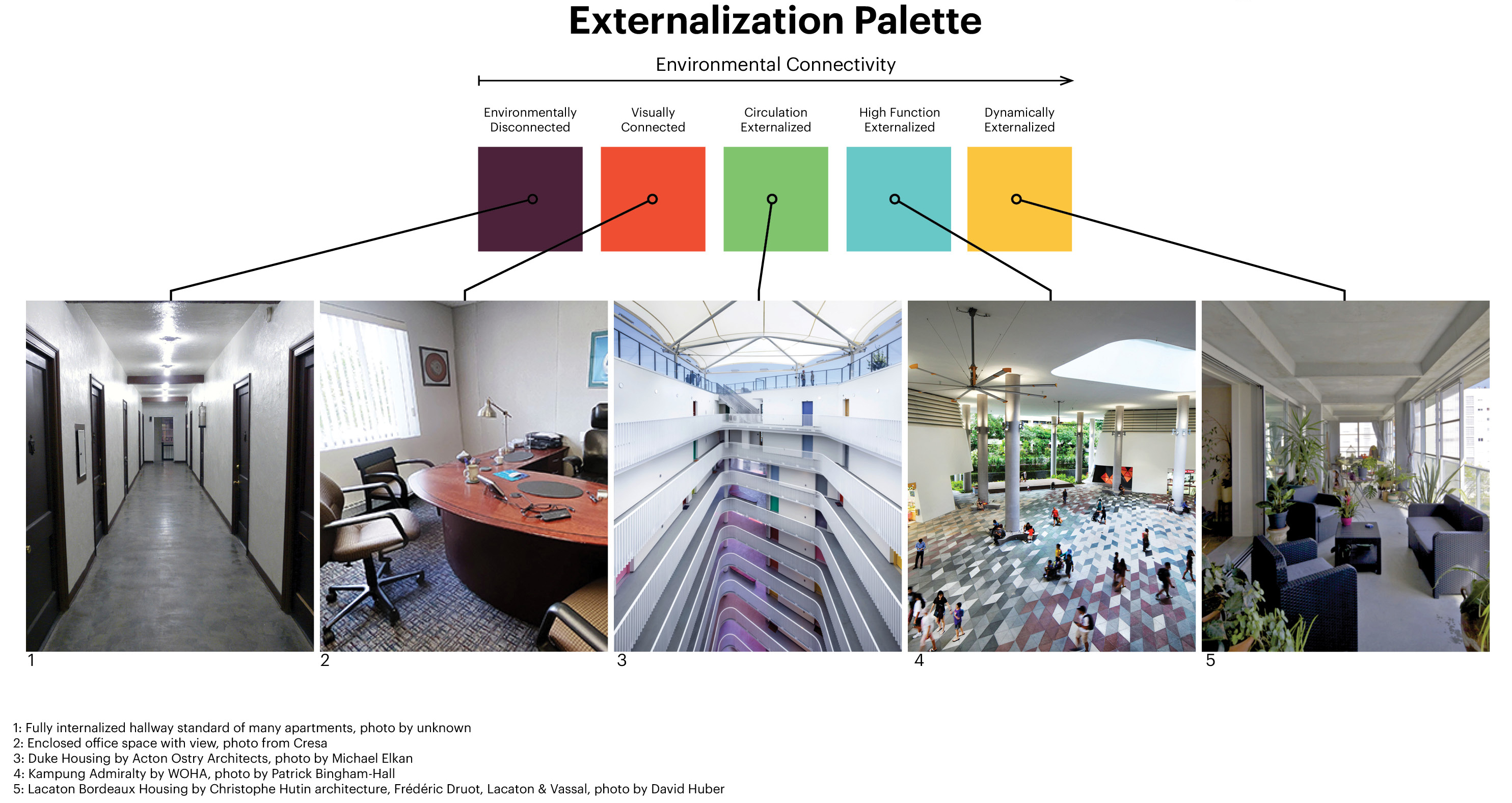

First set of criteria is the environmental connectivity of building programming - based on how the space is sealed, how much daylight is available, and what kind of activity takes place in these spaces.

Why is environmental connectivity important?

This could result in a significant amount of energy savings due to the decrease in conditioned internalized space. Additionally, this allow for an increase in physical activity and circulation, which can increase the overall social connection.

Through environmental externalization, there is added visual richness and connectivity, and well as auditory and sensory richness. This allows for the community to gain a sense of vibrancy through architectural design.

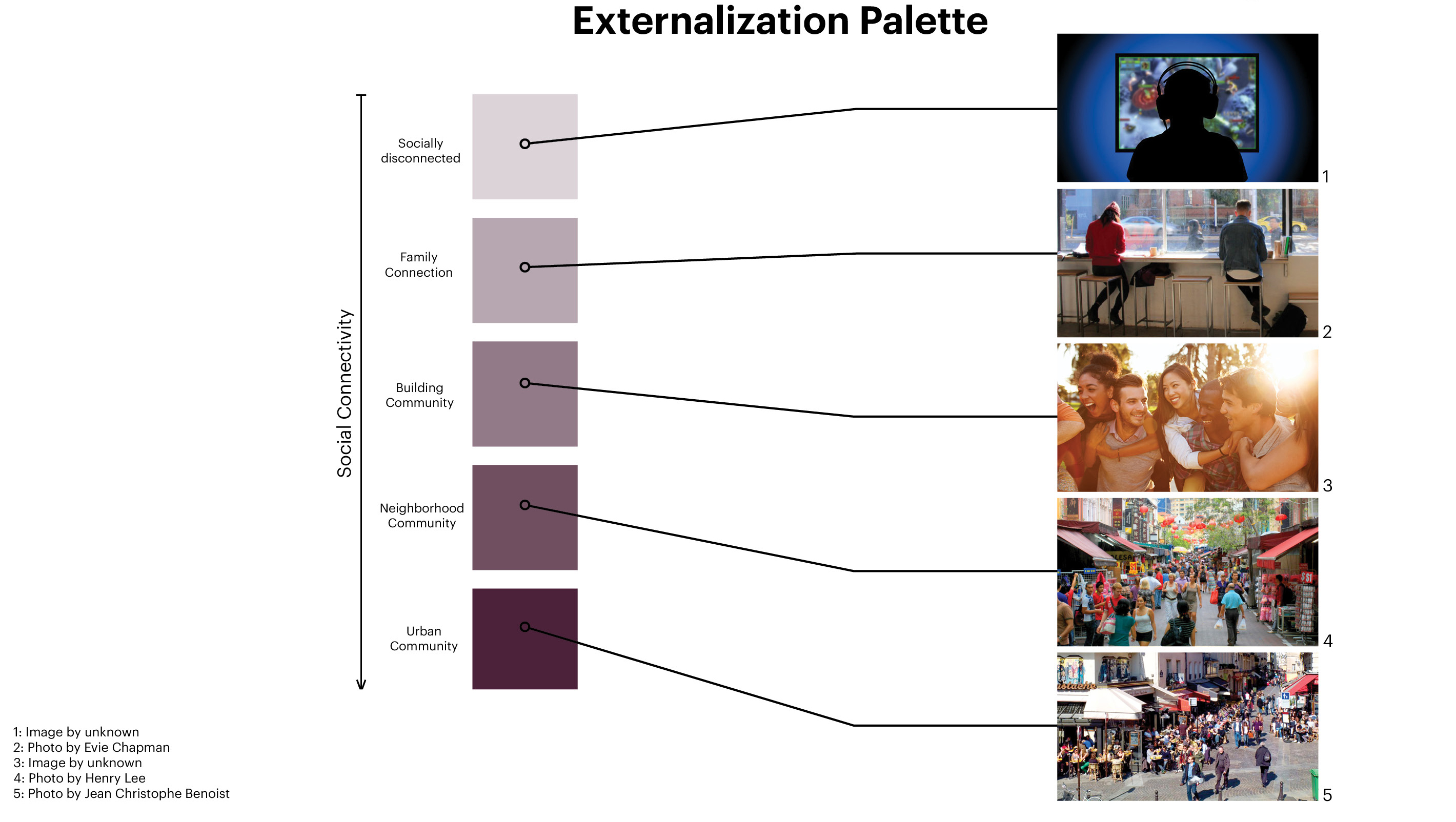

Second set of criteria is the social connectivity of building programming - ranging from individual and disconnected to urban community connectivity.

Why is social connectivity important?

The increased social connections allow for the success, resiliency, and longevity of the externalization strategies through increased social connections, an increase in the amount of outdoor activities, and allow for increased socio-cultural richness.

Additionally this encourages people to communicate and develop a level of tolerance through a sense of community, which can increase the community resiliency in times of crises such as the current COVID-19 pandemic.

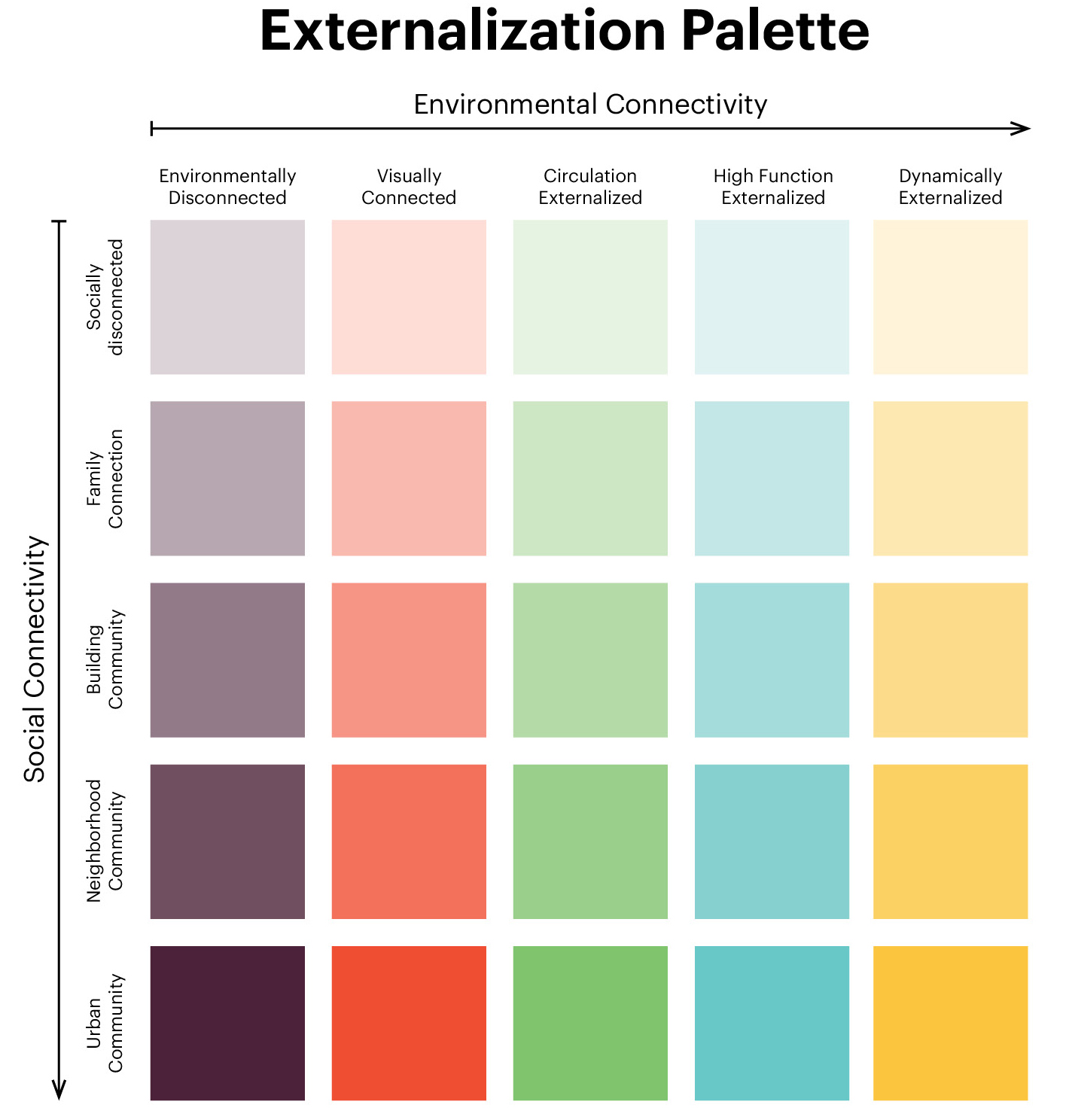

Externalization Palette

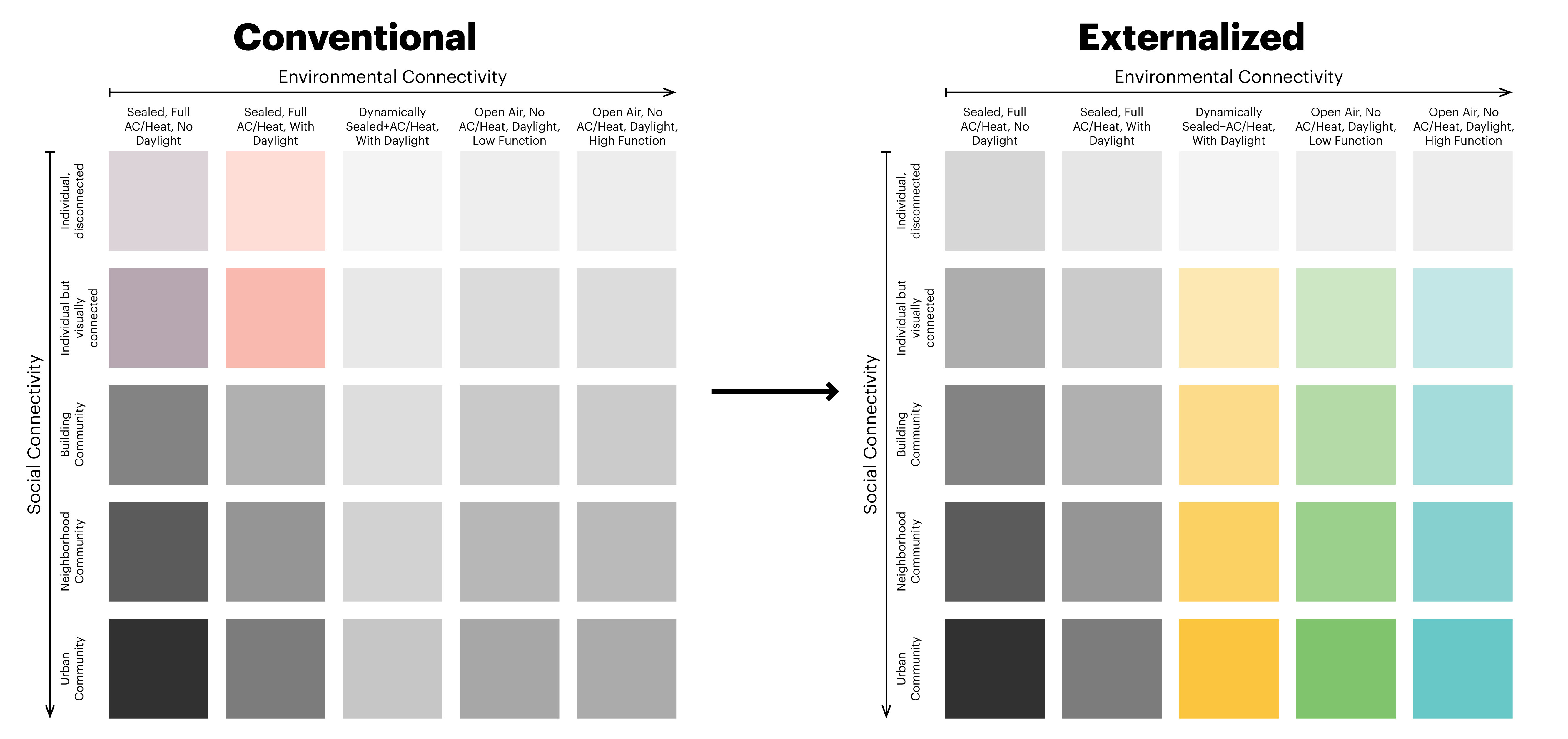

The full externalization palette when both the environmental connectivity and social connectivity are overlapped to create a larger palette that can then evaluate architectural design through this color schema.

In doing so, it allows for immediate understanding of a design's externalization quality in regards to its social and environmental considerations and creates a set of vocabulary for building program externalization that can then evaluate architectural design through the criterias of environmental and social connectivity.

So how do these ideas translate into existing architectural design?

So how do these ideas translate into existing architectural design?

Shown below are 2 case study examples ( more detailed research forthcoming in publication ) that demonstrate the vocabulary ideas of the externalization palette, and highlight some notable differences for 2 healthcare typology and mixed use typology examples.

Photos taken by: Frank Oudeman (NY Presbyterian), Khoo Teck Puat Hospital (Khoo Teck Puat), Tom Harris (40th Tenth Ave), K. Kopter, Vivian Loftness, Patrick Bingham-Hall(Kampung Admiralty)

Additionally, preliminary analysis were conducted to find possible correlations and patterns through a coding exercise. Eight case studies and 2 conventional examples were analyzed based on the environmental connectivity from the externalization palette (social connectivity forthcoming) and notable patterns and findings could be derived from the process.

Based on the externalization ratio breakdown and the key findings derived from this research, it is evident that there are distinct differences between the conventional approach to architectural design and externalized approach. We should shift our way of designing architecture from the conventional to the externalized (as shown below) to design in social and environmental resiliency and connectivity.

Additionally, there are building programs that had more opportunities for externalization based on the case study research.

“

By understanding both the vocabulary and the types of building programs to externalize, how can externalized architectural forms enable human-nature connectivity, and what is the vocabulary for such architectural design? ”

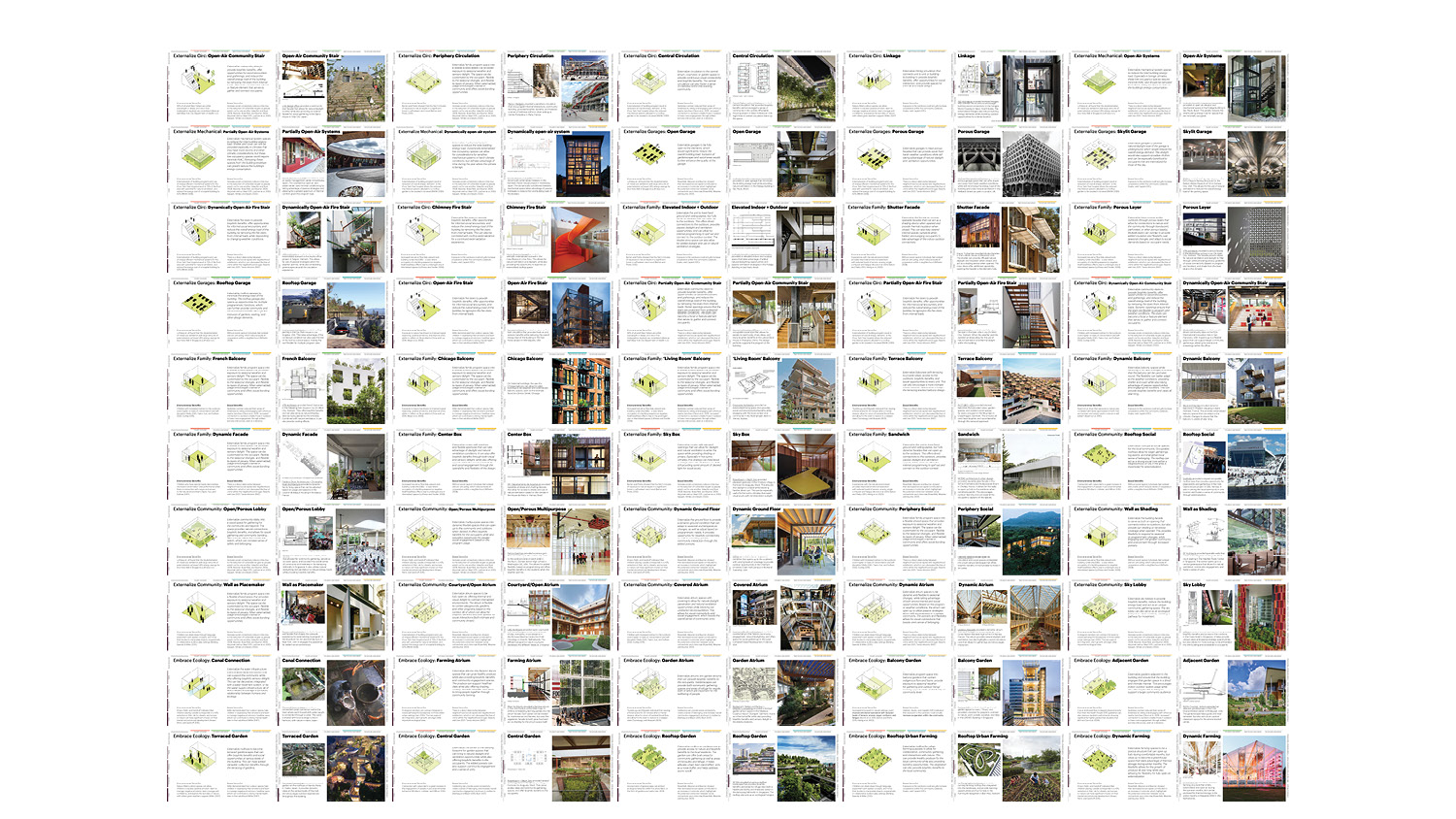

Through the analysis of over 30 case studies across different climate types, typologies, and geographical locations, it was found that most new constructions prevailed in the conventional 4 blocks, while successfully externalized designs had spaces that were in the lower 12 quadrants. Based on the research, it is evident that there are distinct differences between the conventional approach and externalized approach. We should shift our way of designing architecture from the conventional to the externalized to design in social and environmental connectivity. In order to do that, I have developed an externalization taxonomy of 50 strategies to help designers to shift their approach from an internalized perspective to externalized.

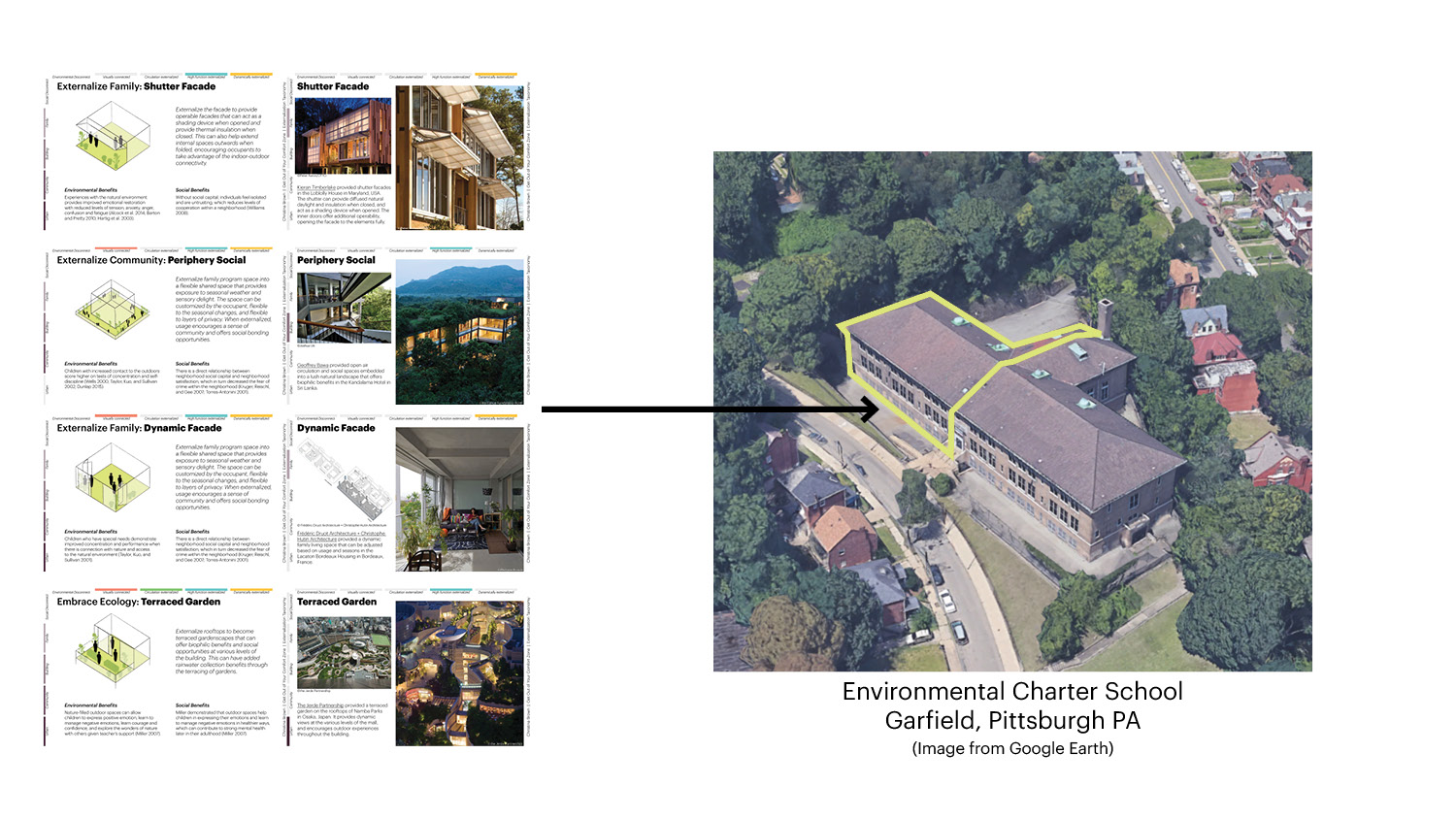

The taxonomy distinguish specific architectural design elements that externalize various building programming with varying environmental and social impacts. This begins to create a series of design strategies that can then be implemented into architectural design to allow for imbedded externalization. The strategies attribute to various parts of the externalization palette, allowing for a diverse set of strategies that can provide varying amounts of environmental and social connectivity based on the program and context of a project.

To view the 50 taxonomy cards in detail or to download a printable version of the taxonomy, please click here.

To view the 50 taxonomy cards in detail or to download a printable version of the taxonomy, please click here.

What is the immediate difference in the strategy quality? Comparisons are made for specific taxonomy strategies to demosntrate the impact and value of externalization even at small interventional scales.

Photos taken by: Philippe Ruault (Lacaton), 2020 Beaux Arts (SkyVue), Peter Aaron/OTTO(Loblolly)

Photos taken by: Bruce Coleman (Porter), Hiroyuki Oki (Stacking Green), Yercekim Architectural Photography (Intertech), KLOOK (Pompidou)

Photos taken by: Yercekim Architectural Photography (Intertech), SsD (Songpa), Mitar Mitrovic (New Belgrade), Frank Ockert (IBN)

How can these strategies be applied to and improve architectural design?

And what are the environmental and social impacts that can be achieved through the inclusion of externalized building programming within architectural design?

How can we shift architectural design from the conventional into the externalized?

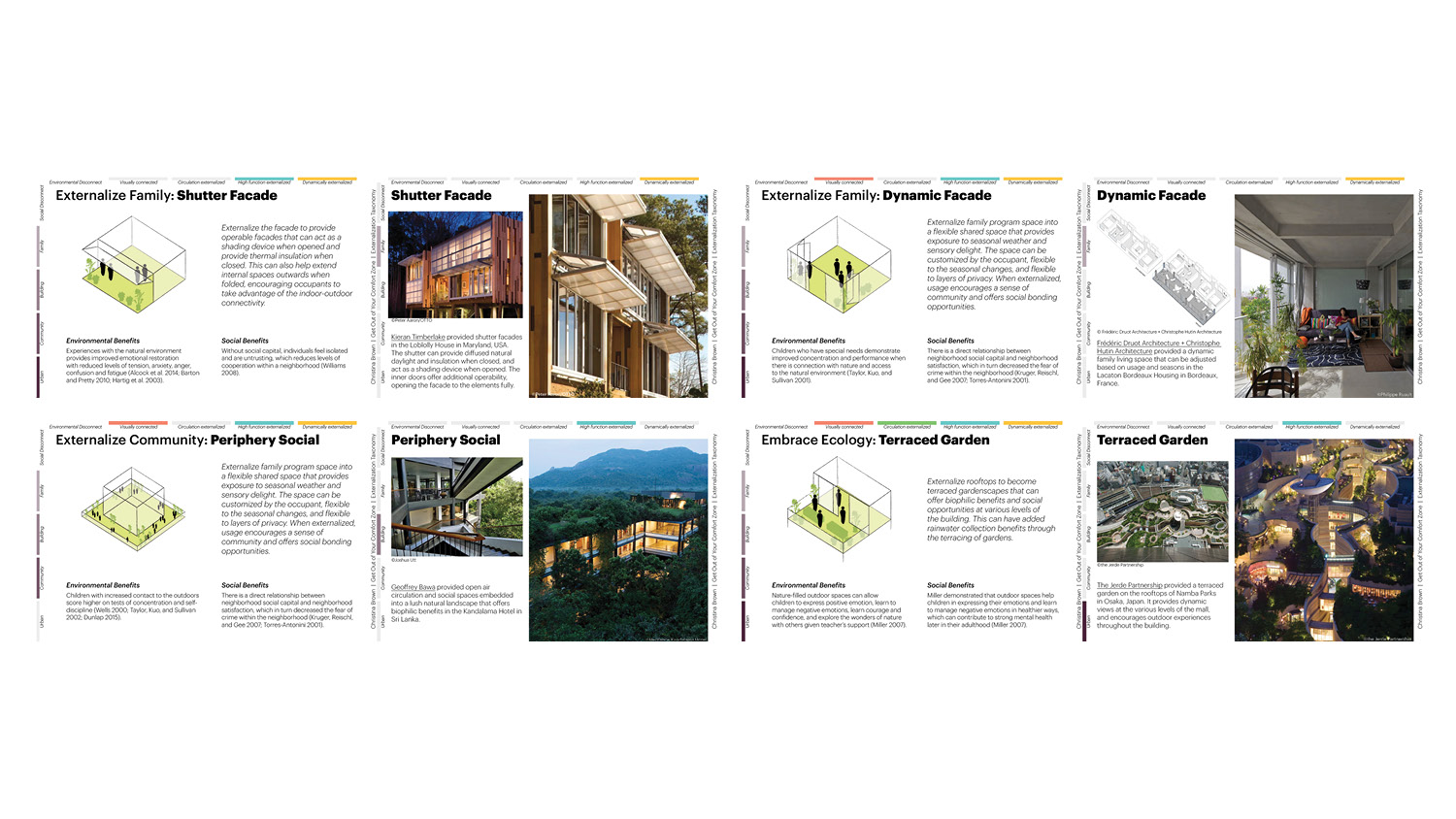

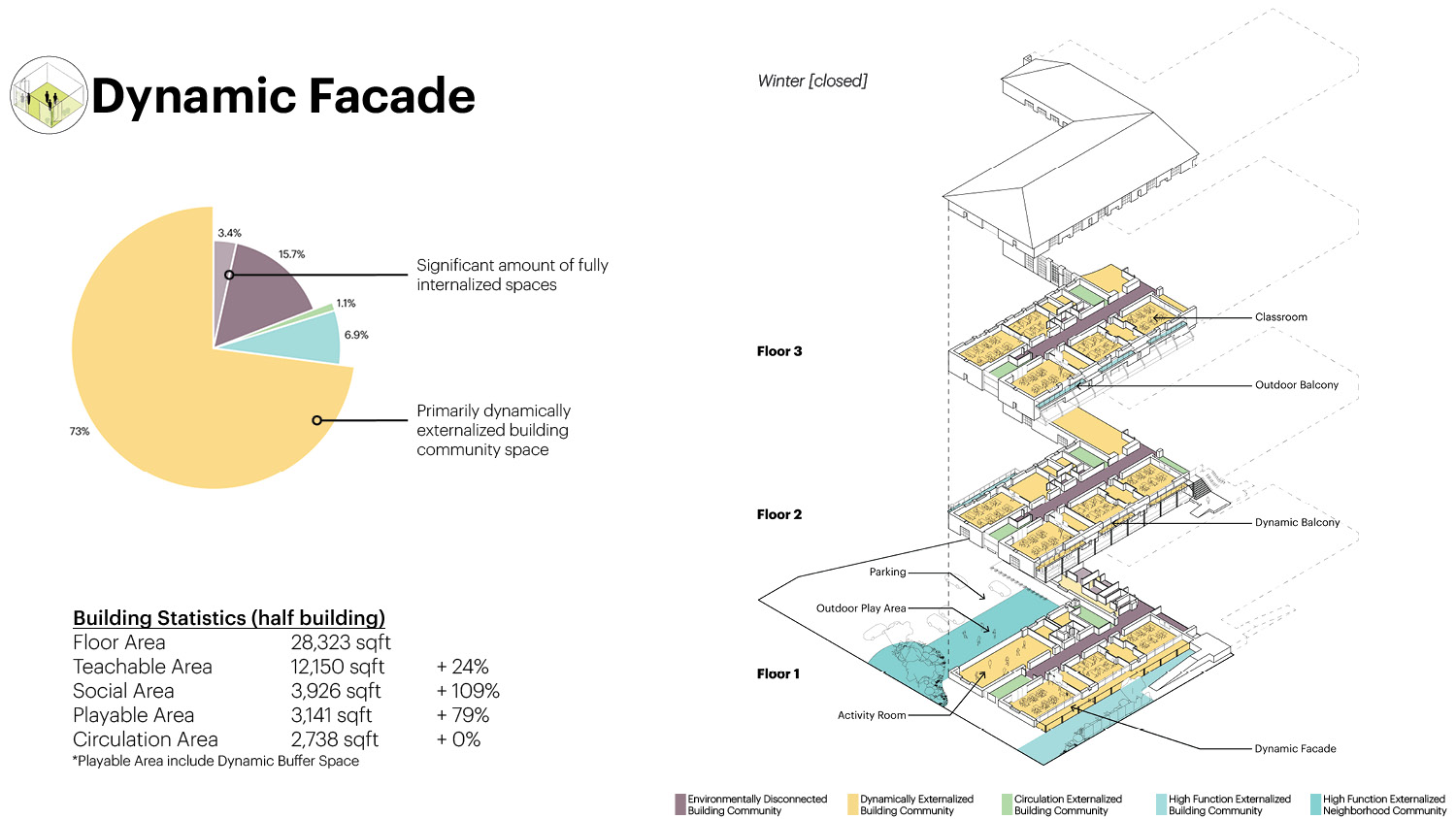

To answer these questions, 4 specific strategies were chosen and applied to a case study in Pittsburgh to better understand its impact on the building’s design, its daylighting and energy performance, and lastly its experiential impact. The four specific strategies chosen where the shutter facade, dynamic facade, periphery social, and terraced garden strategies.

These 4 strategies were applied to the Environmental Charter School in Garfield to explore the value of externalization in architectural design. Due to the constraint of time, I focused on only the western half of the building.

The Environmental Charter School (ECS) in garfield is a middle school that has 6th to 9th grade students. The school has an unique out-the-door learning approach that greatly values outdoor learning environments and space for the community (as shown in the school’s mission statement below).

“The ECS Middle School houses students from sixth grade through eighth grade with ninth grade opening in the Fall of 2020.

Built in 1914 and located in the Garfield community, the Middle School has easy access to public transit and bike trails. The building sits on an almost 3 acre site and accommodates the school’s unique out-the-door learning approach.

In an urban location, the property has upper and lower green spaces outside of the school to double as outdoor learning environments for the students and a space for the community. Several community spaces and parks are within walking distance. “

Built in 1914 and located in the Garfield community, the Middle School has easy access to public transit and bike trails. The building sits on an almost 3 acre site and accommodates the school’s unique out-the-door learning approach.

In an urban location, the property has upper and lower green spaces outside of the school to double as outdoor learning environments for the students and a space for the community. Several community spaces and parks are within walking distance. “

However the existing architecture has sealed windows with internalized spaces that doesn’t encourage students to experience the outdoors. The internalized architecture does not align with the intent and goals of the ECS.

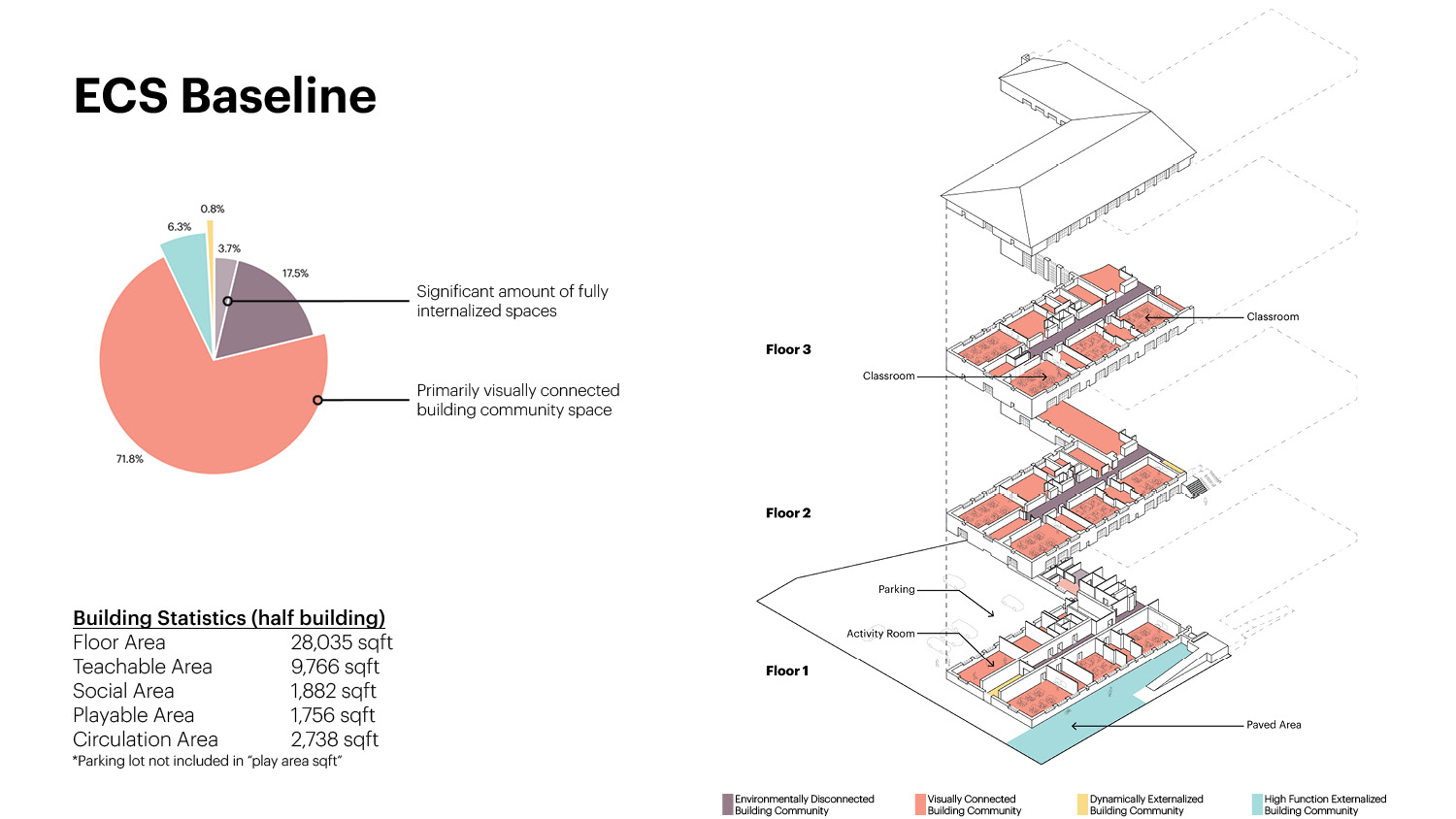

To explore the impacts of externalization further, an understanding of the existing conditions at ECS are needed. First the building externalization ratios and statistics are provided, along with a mapping of the spaces based on program relative to externalization.

Analyzing the current baseline, the school is primarily enclosed with visual connection alone. The paved area and the parking lot is used for students to play, along with nearby green spaces outside of the focused site.

Analyzing the current baseline, the school is primarily enclosed with visual connection alone. The paved area and the parking lot is used for students to play, along with nearby green spaces outside of the focused site.

So what value would externalization bring?

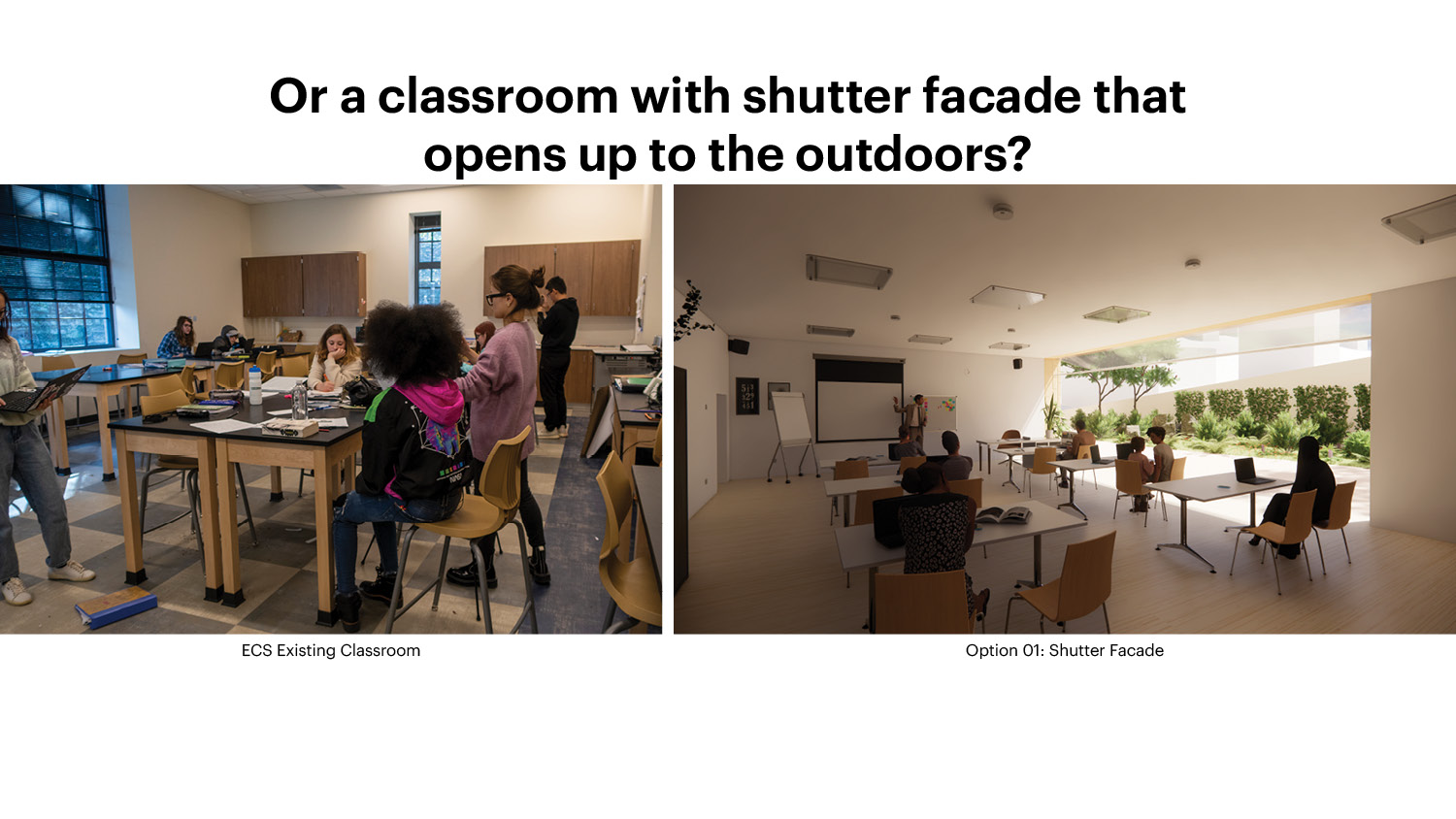

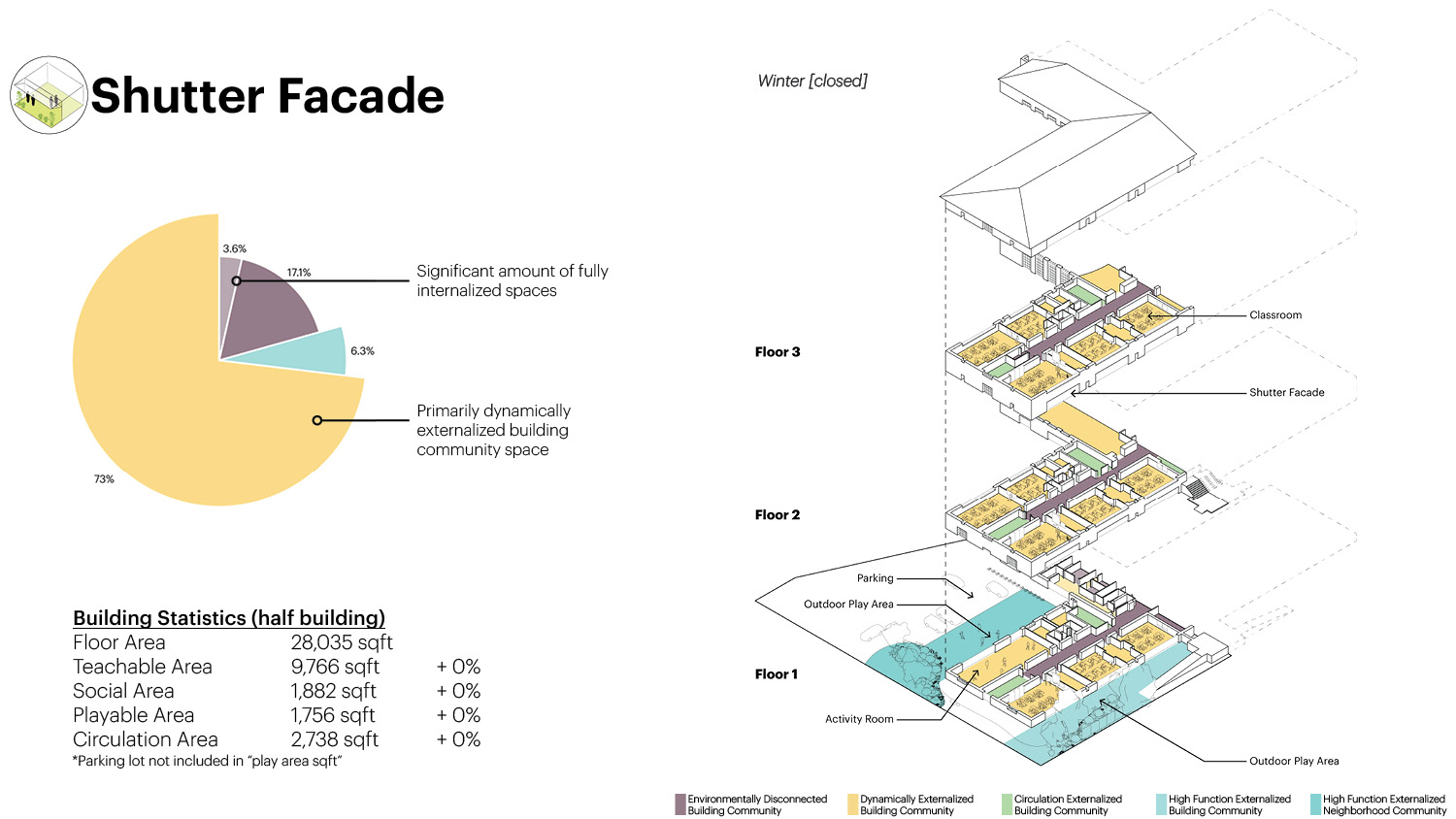

The first strategy - shutter facade - woudl provide operability so students and faculty can take advantage of natural ventilation and connections to the outdoors.

The outdoor play areas are also landscaped and vegetated so students on the ground floor can run out directly from the classrooms. There is still significant amount of fully internalized spaces, though the sealed classroom spaces are now dynamically externalized, offering biophilic benefits that are important to student wellbeing and performance.

And experientially, it can greatly impact how classes are taught and the relationship of students to the outdoors.

![]()

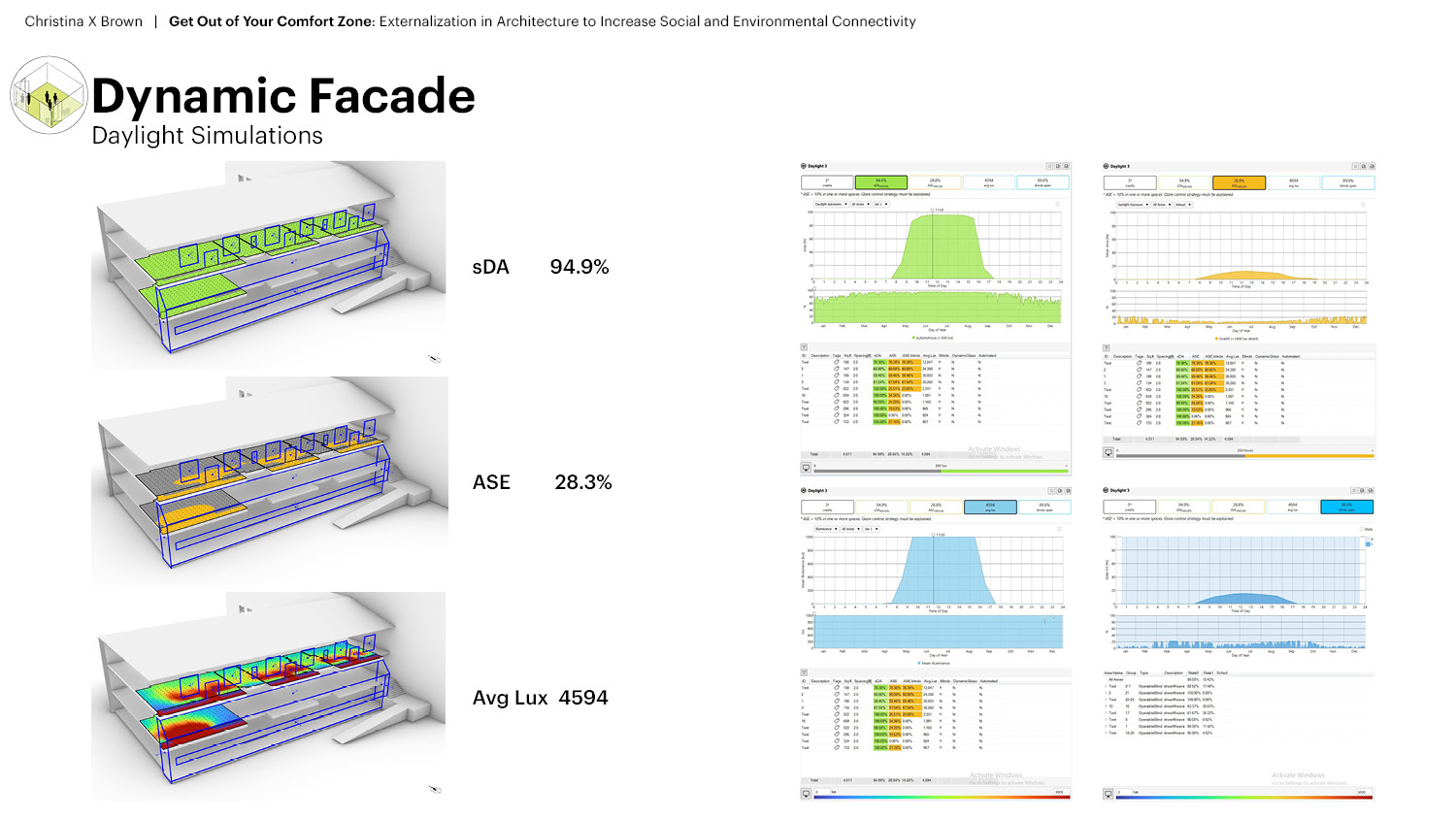

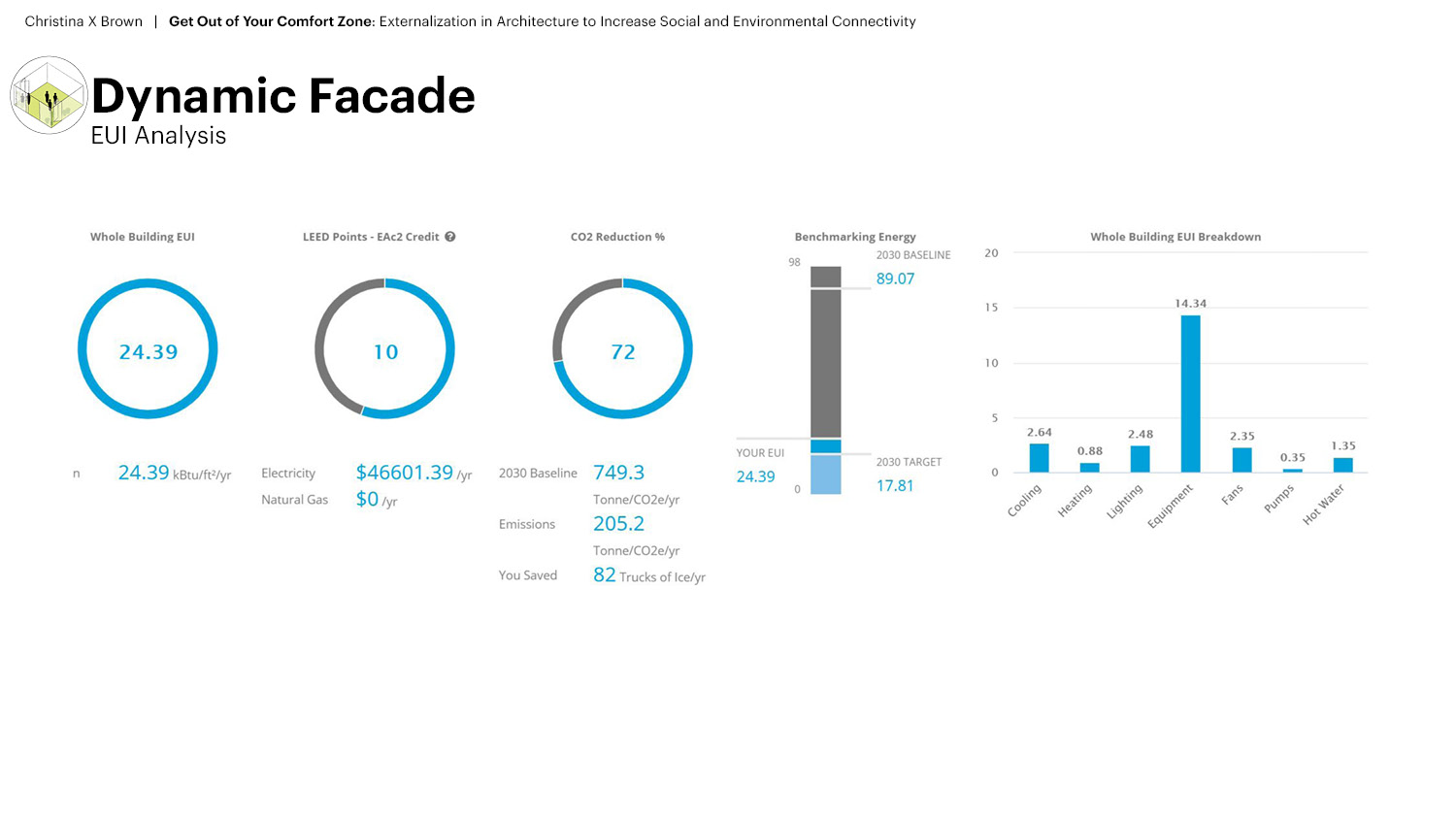

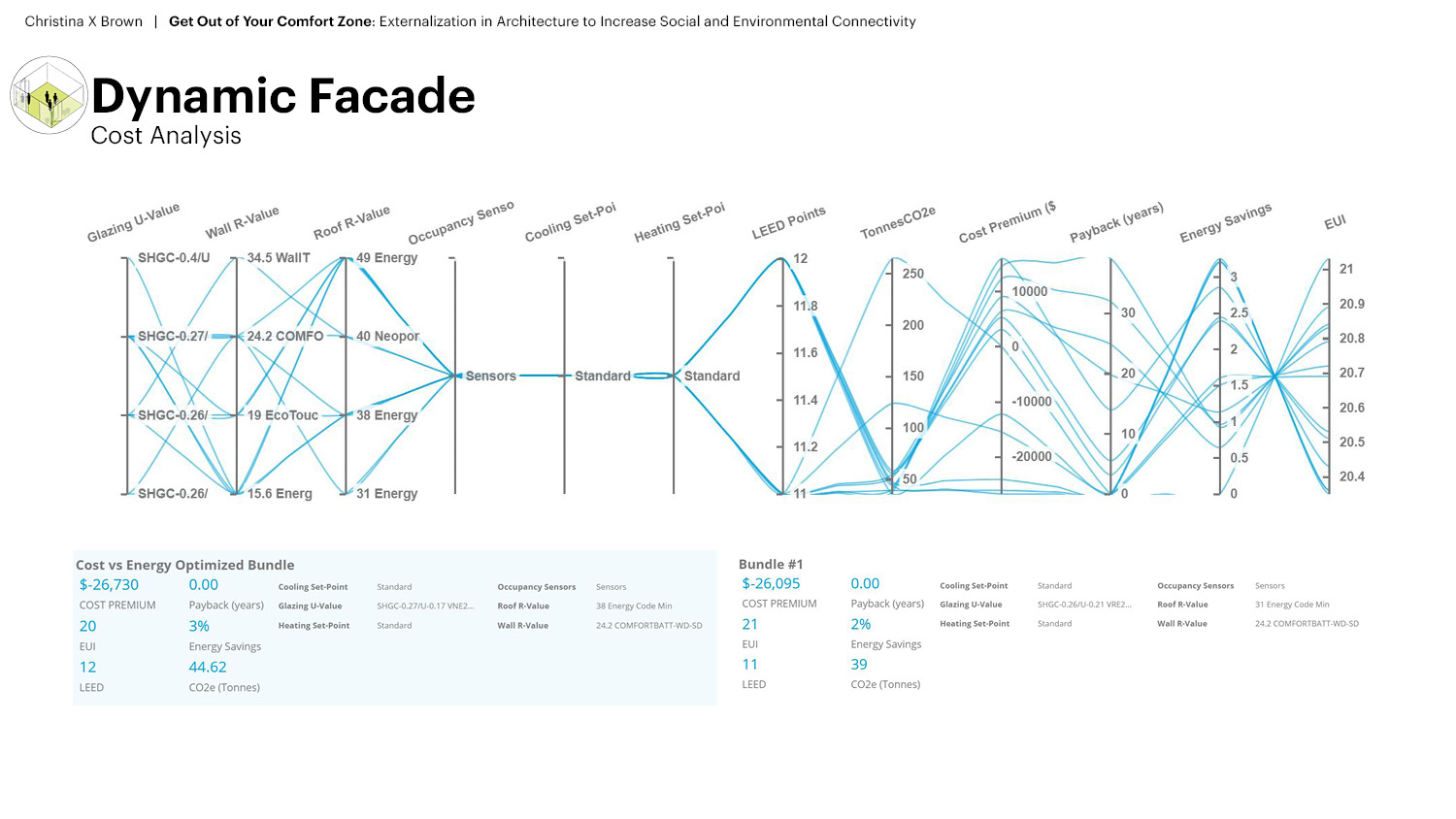

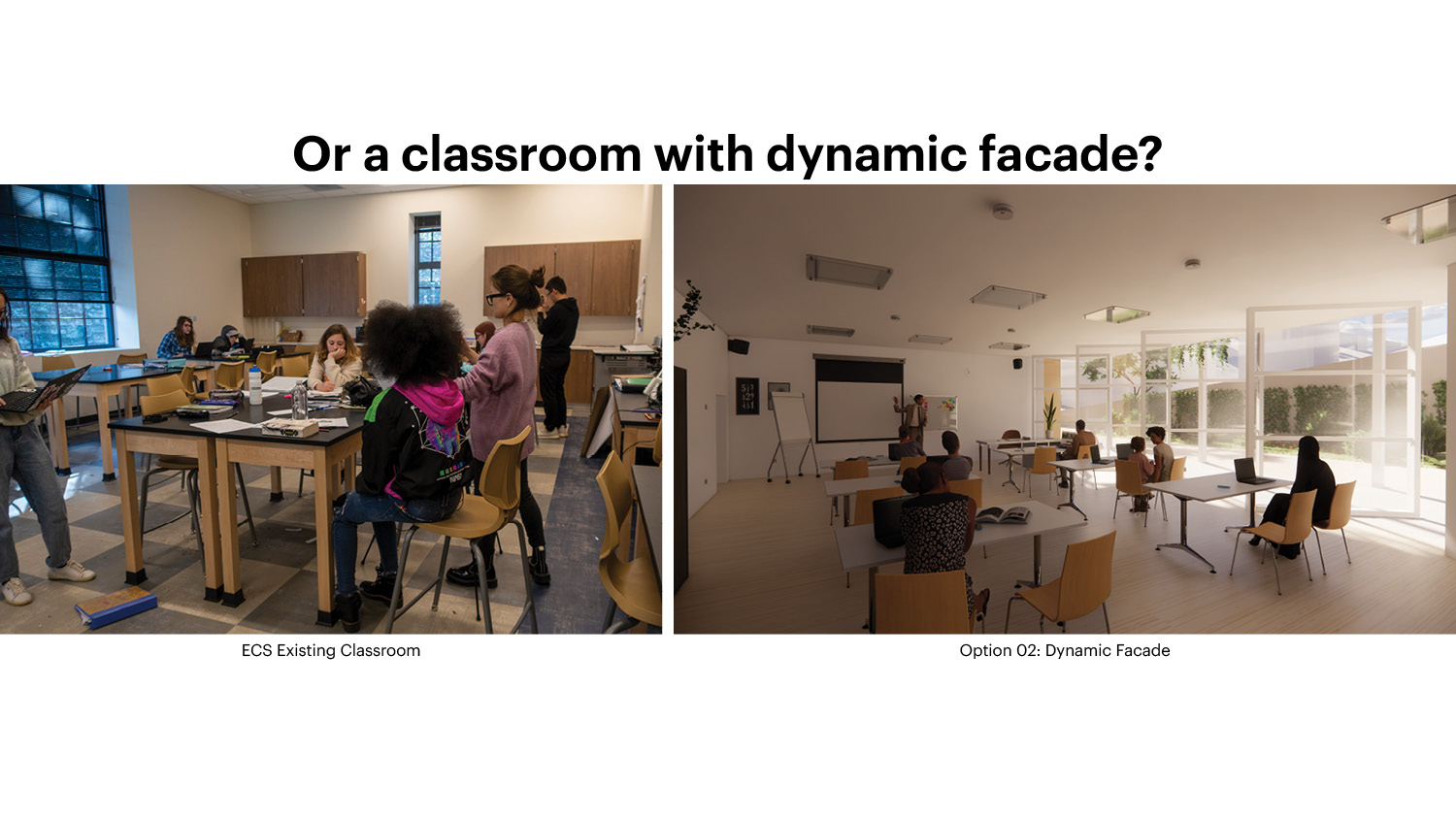

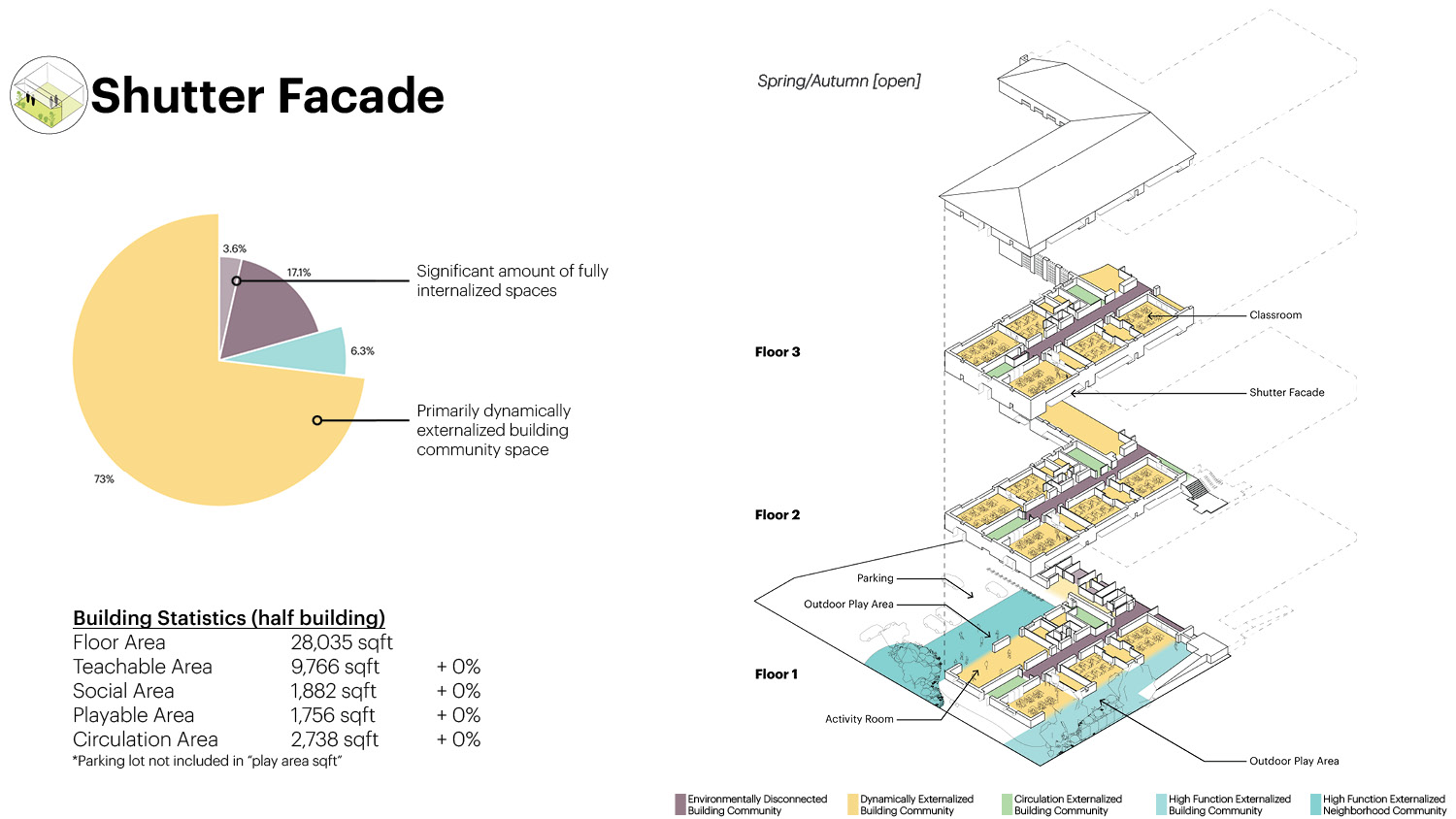

Another strategy with greater alterations to the baseline is the dynamic facade, which provides even more porosity and flexibility into the architectural design.

A dynamic buffer zone is also added on the southern facade to take advantage of thermal capture in winter months.

![]()

This strategy also allows for mostly dynamically externalized spaces, but increases the amount of high function externalized spaces through balconies. This results in great increases in teachable area, social area, and playable area through the added buffer space and balcony additions.

A dynamic buffer zone is also added on the southern facade to take advantage of thermal capture in winter months.

This strategy also allows for mostly dynamically externalized spaces, but increases the amount of high function externalized spaces through balconies. This results in great increases in teachable area, social area, and playable area through the added buffer space and balcony additions.

This offers a very different connection to the outdoors for the students, while still providing many of the externalization benefits.

![]()

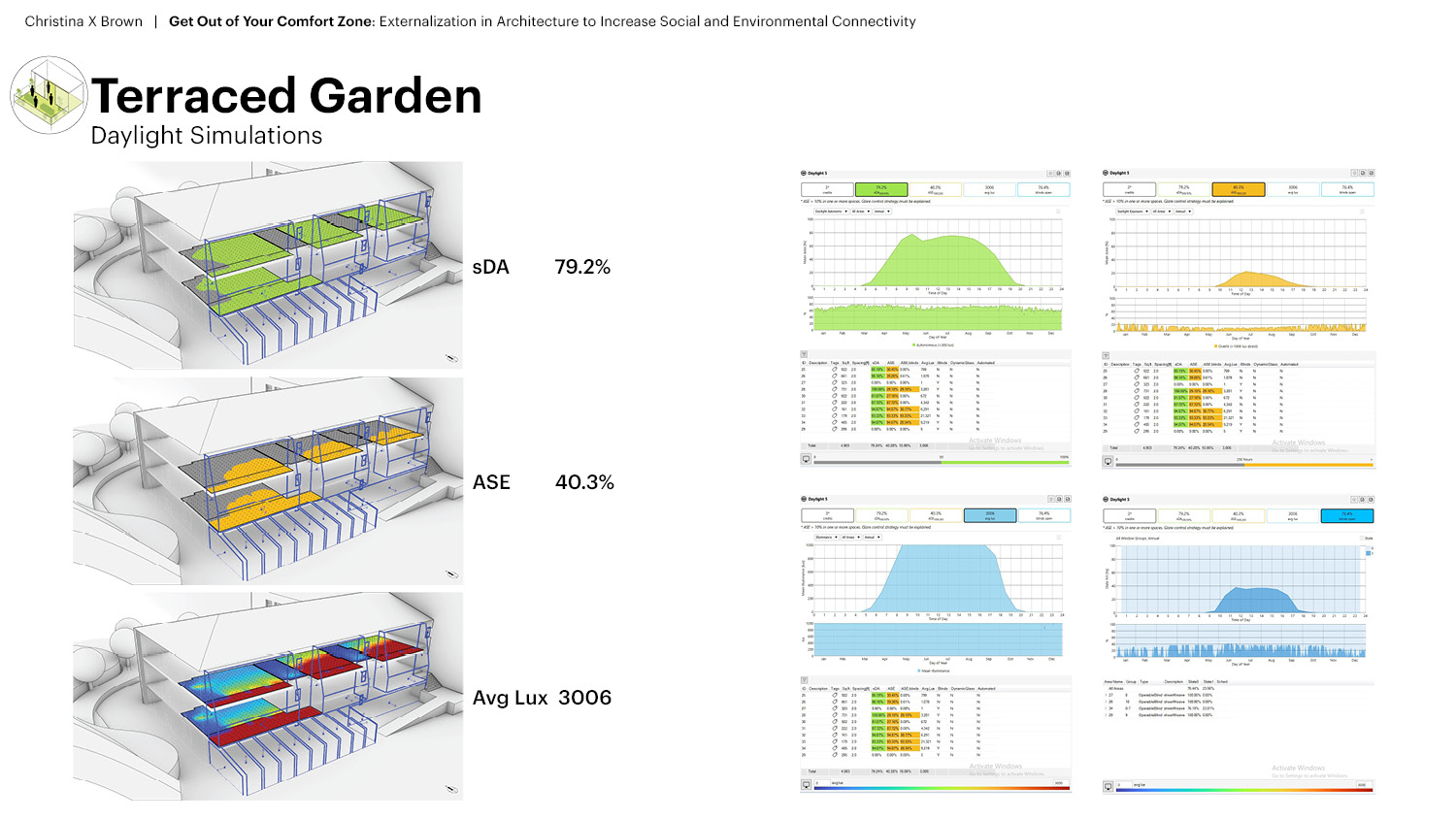

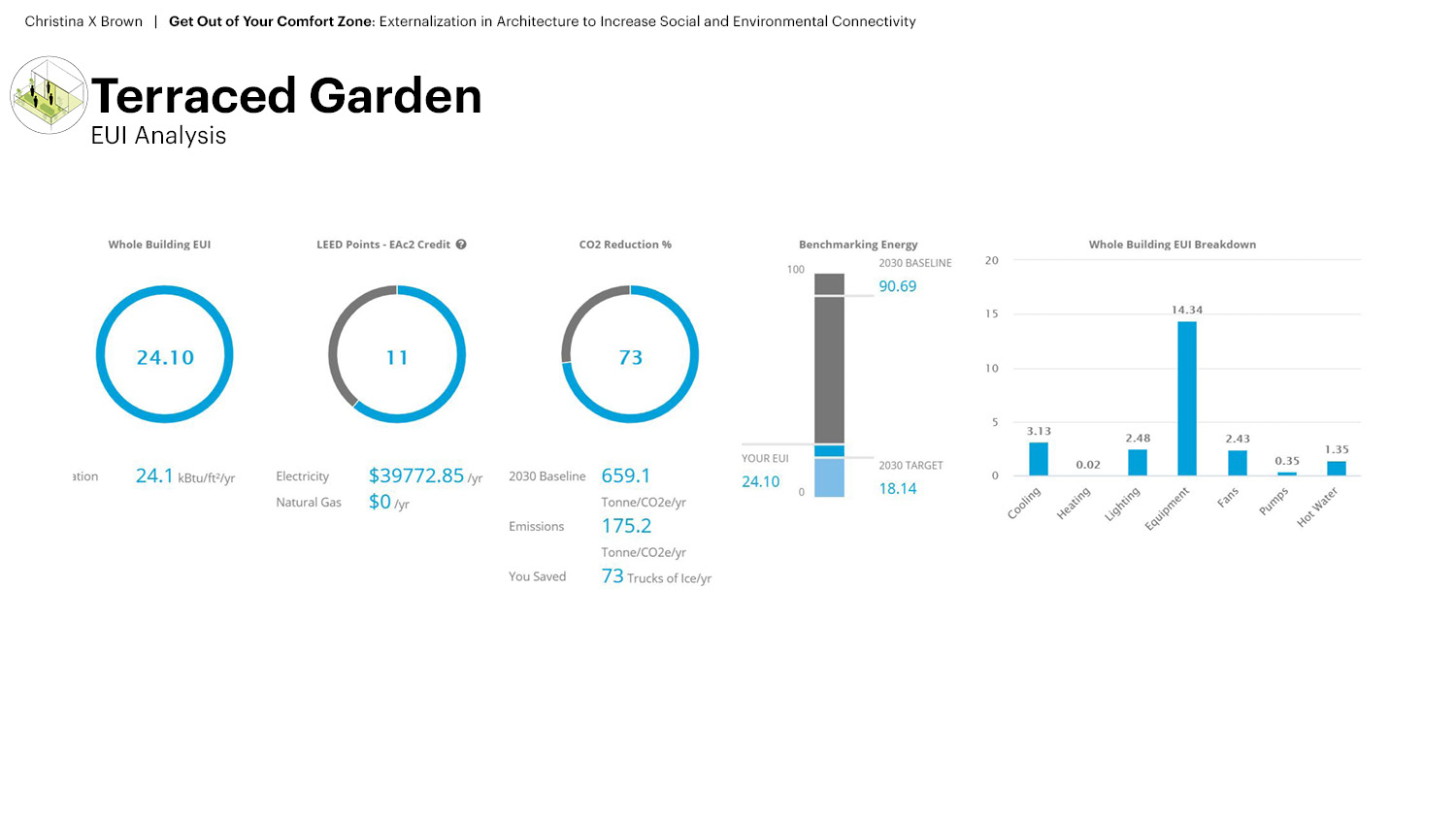

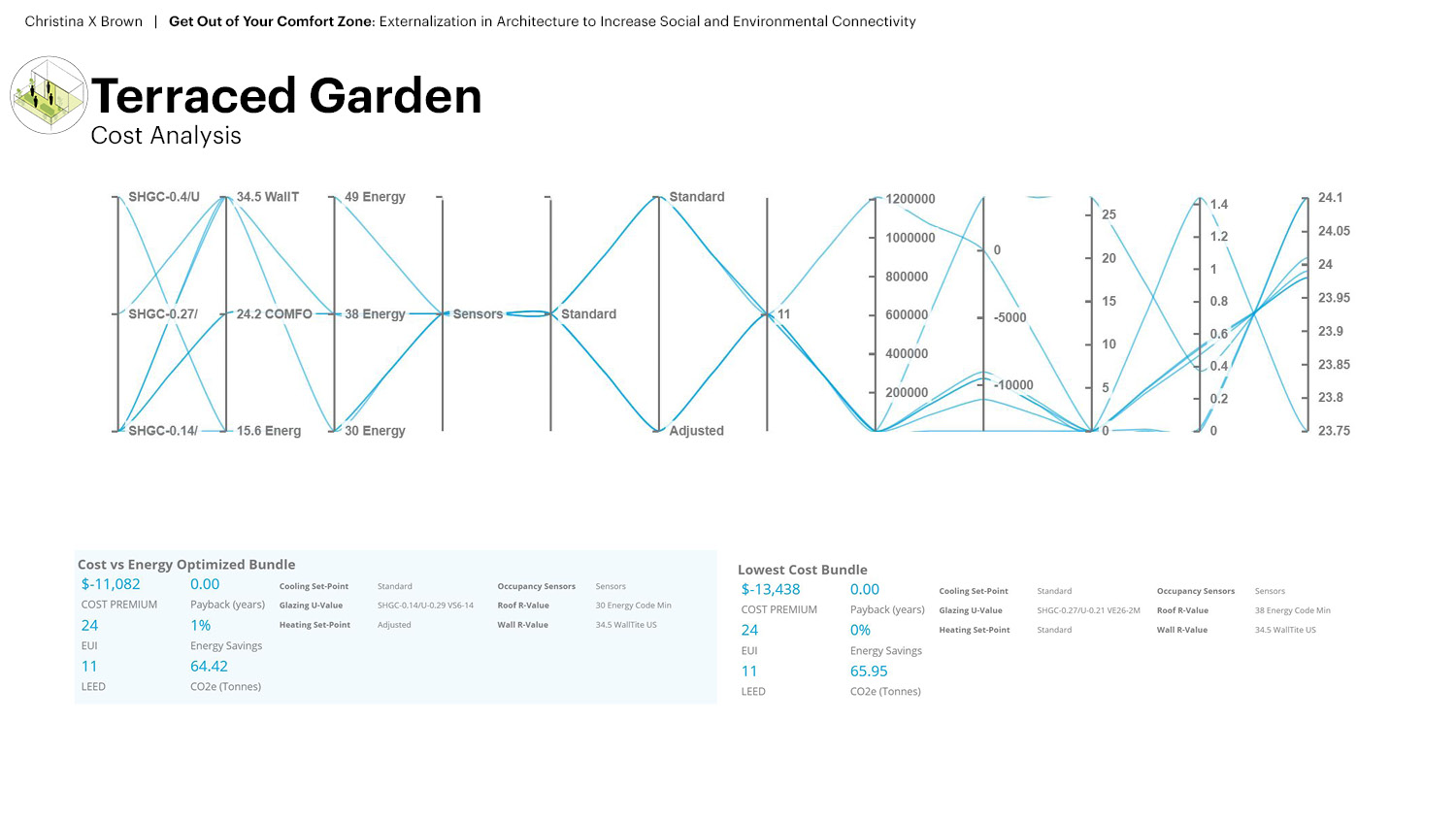

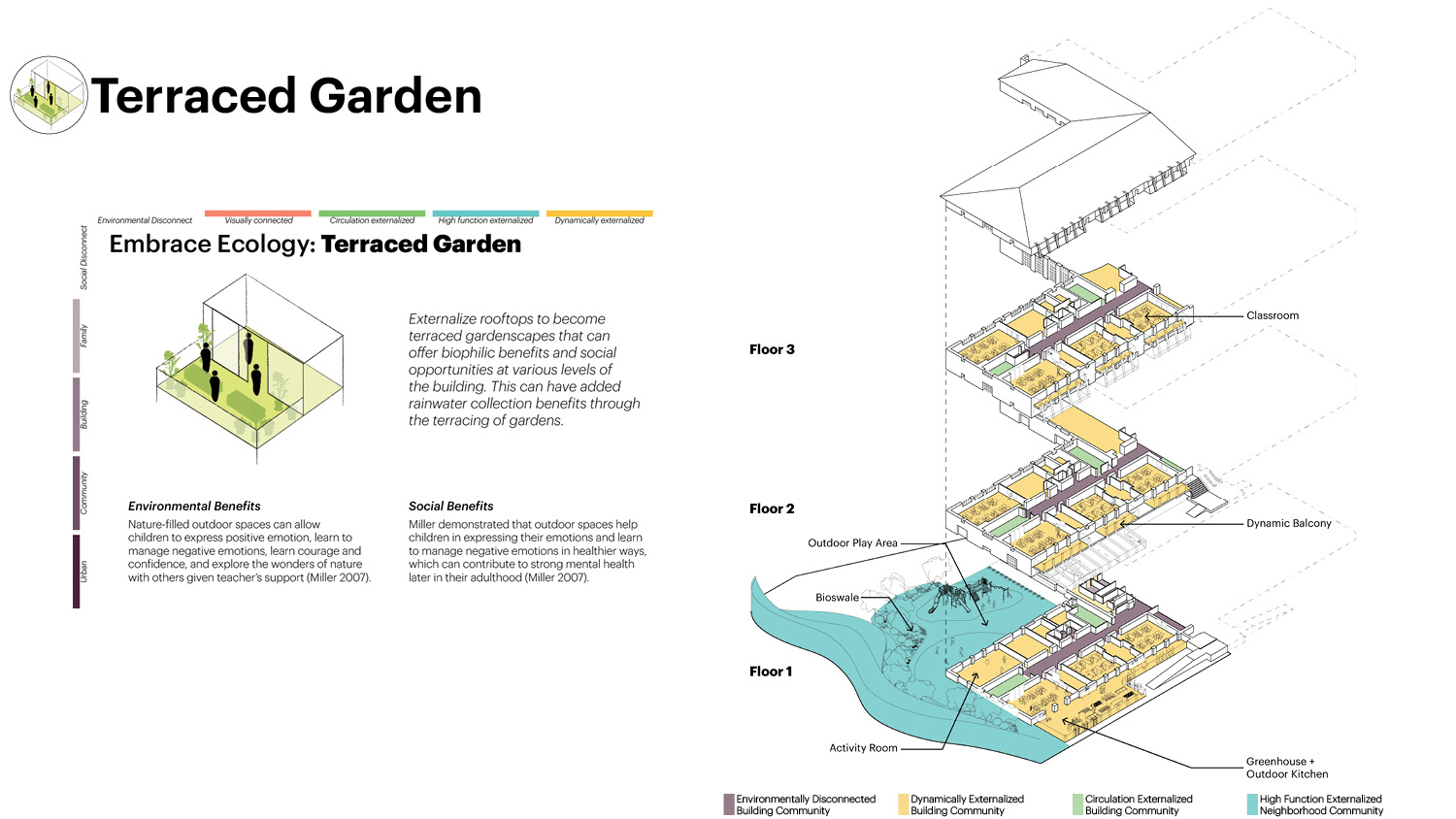

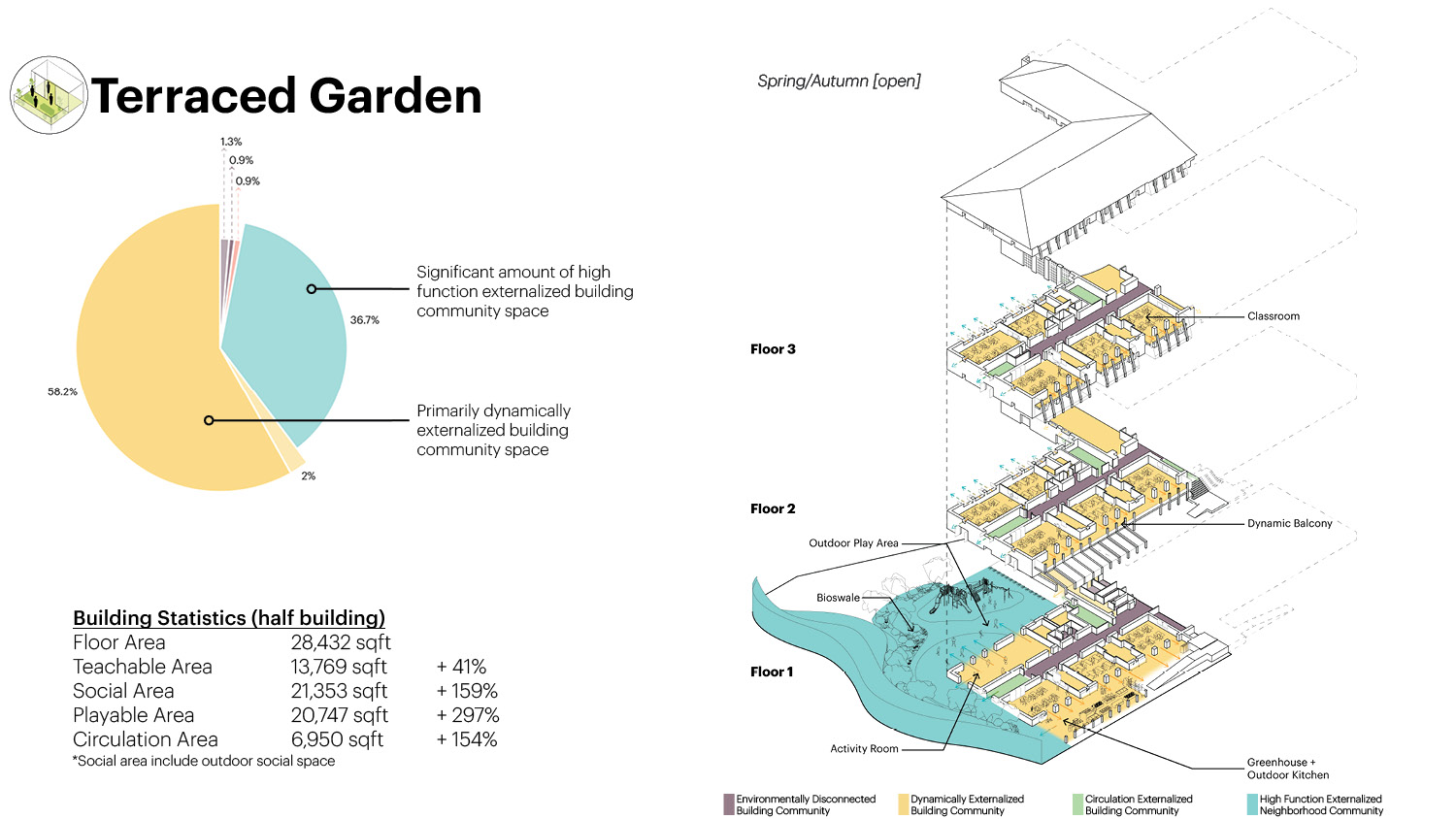

The third strategy is the terraced garden, which aims to embrace ecology while offering both social and biophilic benefits.

In this iteration there is a terraced landscape on the western side that embraces a bigger outdoor play area for the students. The parking lot is in return moved offsite to the adjacent openspace. The southern paved area is now transformed into a flexible garden space and outdoor kitchen space with balconies on the second and third floors.

![]()

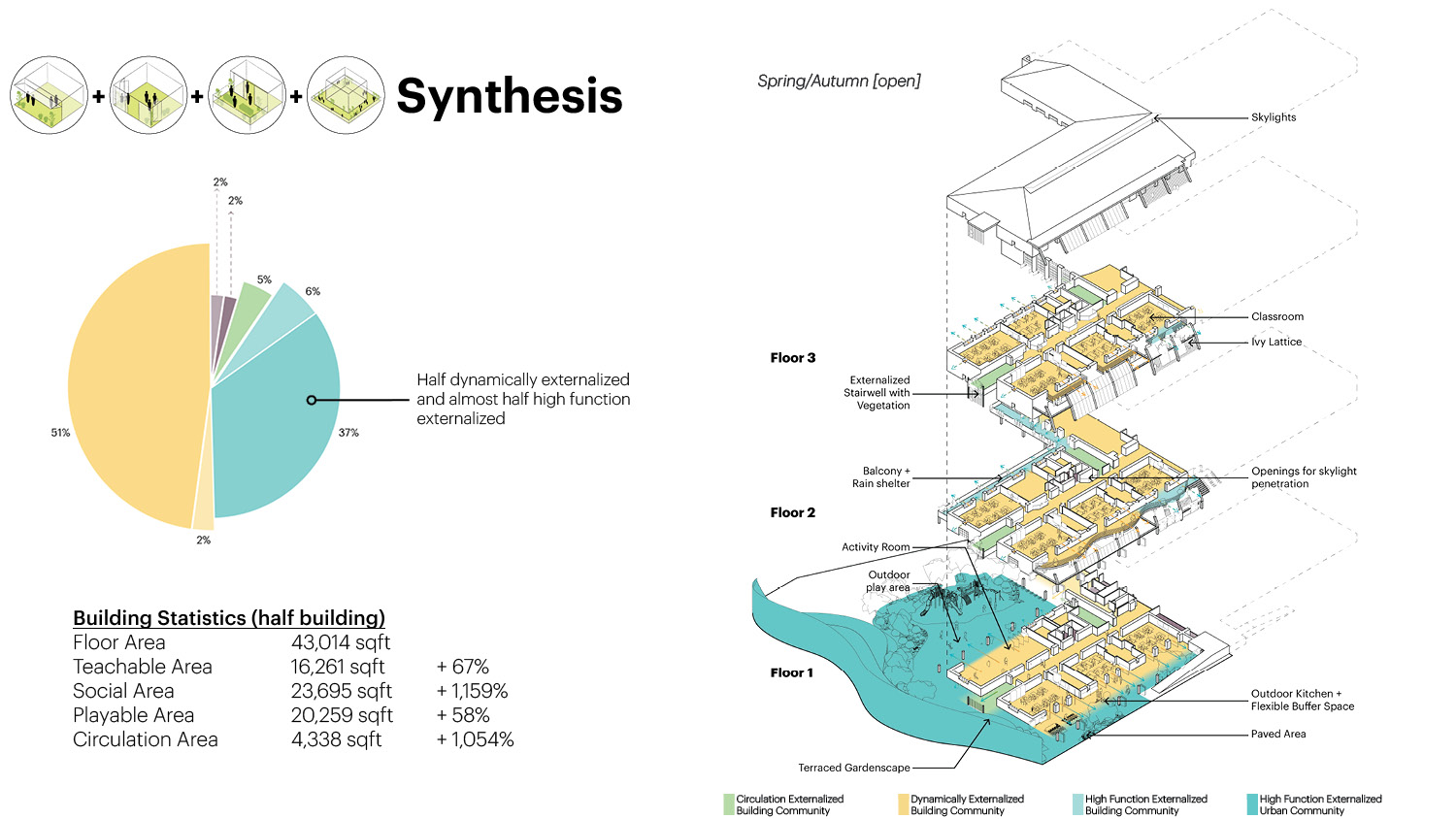

This approach greatly increases the amount of high function externalized spaces, with the majority of the design being either dynamically or fully externalized to the outdoors. This also results in incredible increases in the total teachable area, social area, playable area, and circulation in the outdoors.

In this iteration there is a terraced landscape on the western side that embraces a bigger outdoor play area for the students. The parking lot is in return moved offsite to the adjacent openspace. The southern paved area is now transformed into a flexible garden space and outdoor kitchen space with balconies on the second and third floors.

This approach greatly increases the amount of high function externalized spaces, with the majority of the design being either dynamically or fully externalized to the outdoors. This also results in incredible increases in the total teachable area, social area, playable area, and circulation in the outdoors.

And experientially, this could greatly impact the ECS curriculum and allow for the teachers to provide more hands on activities with the integration of farming, gardening, and cooking.

![]()

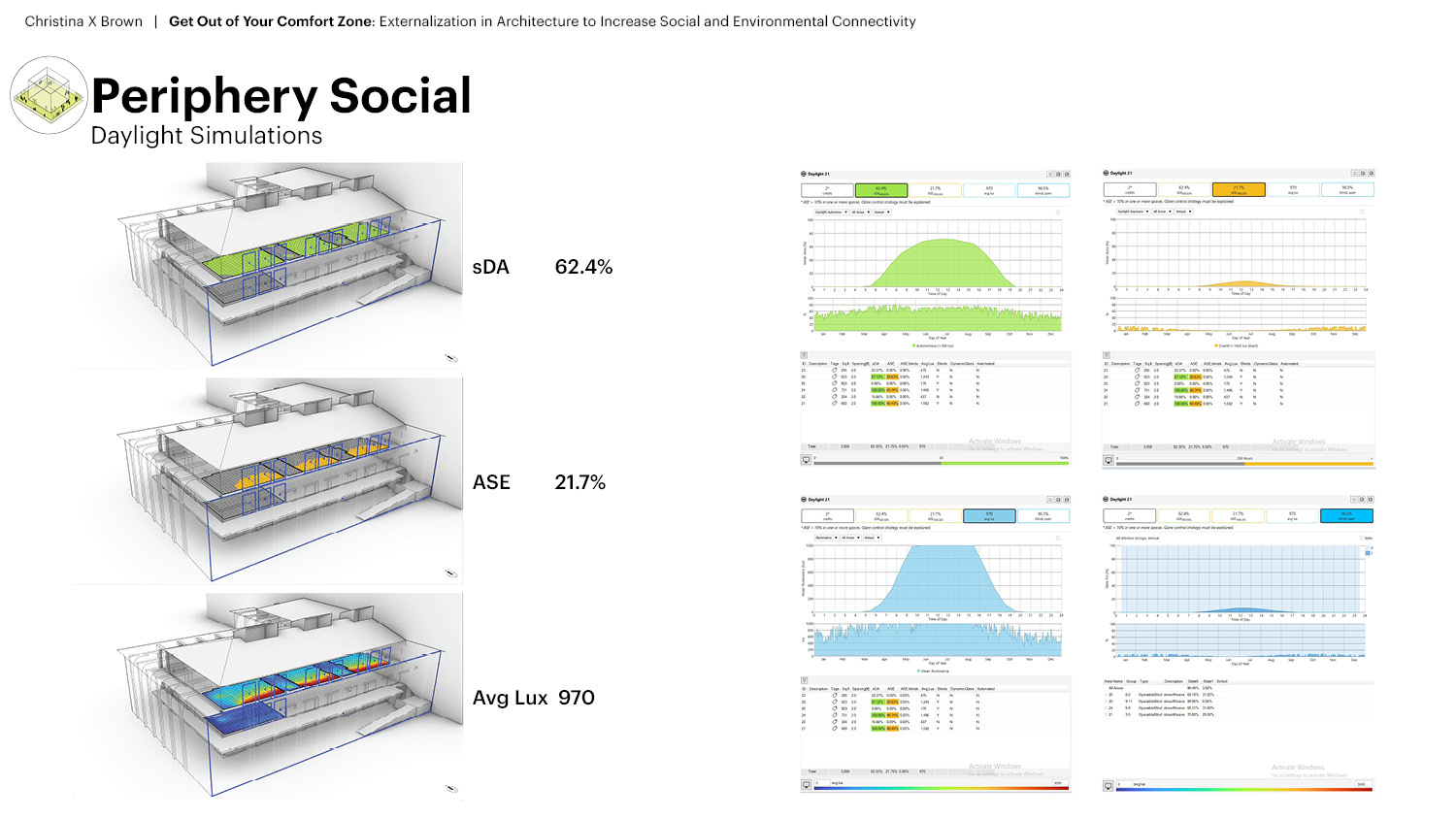

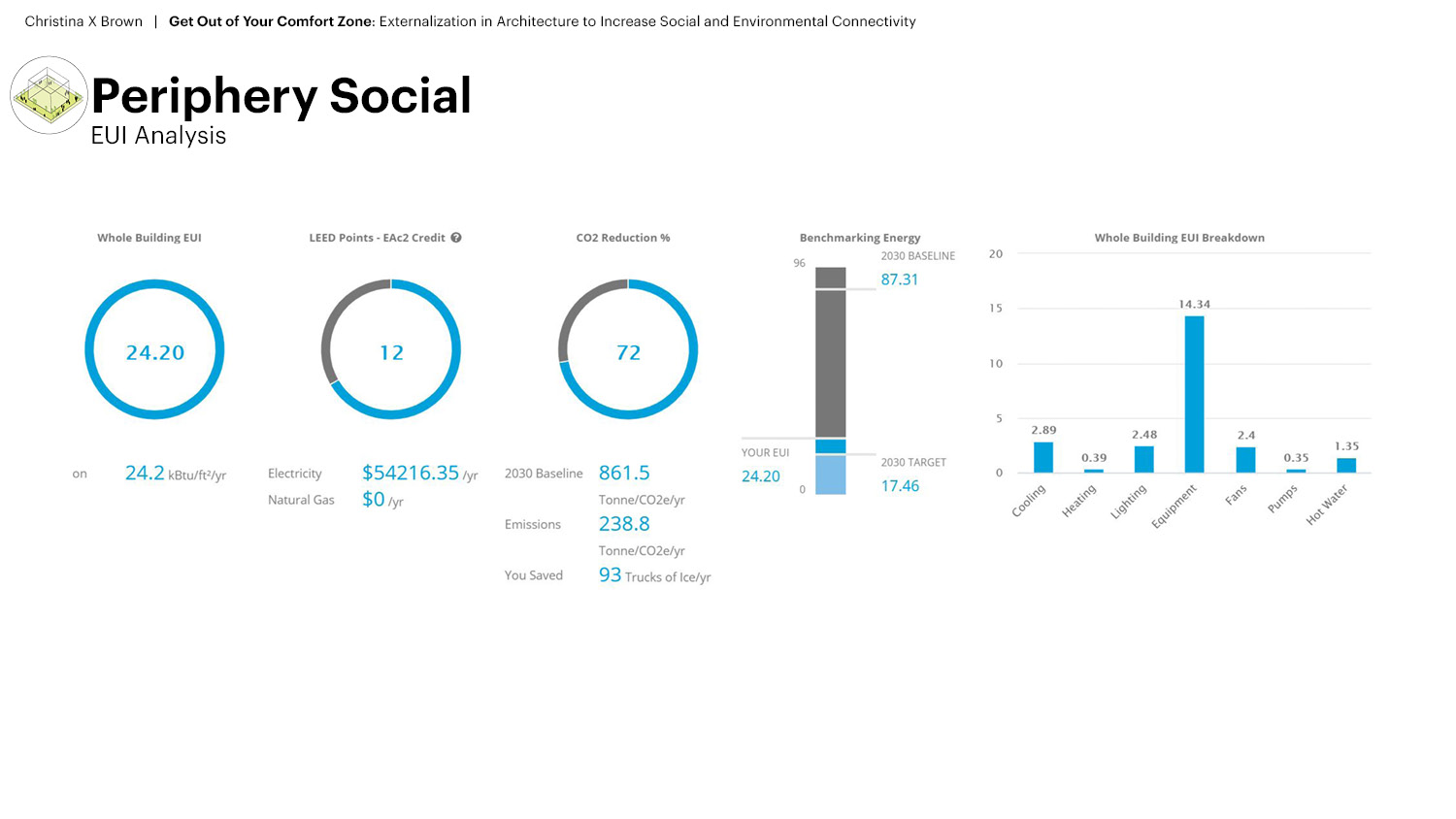

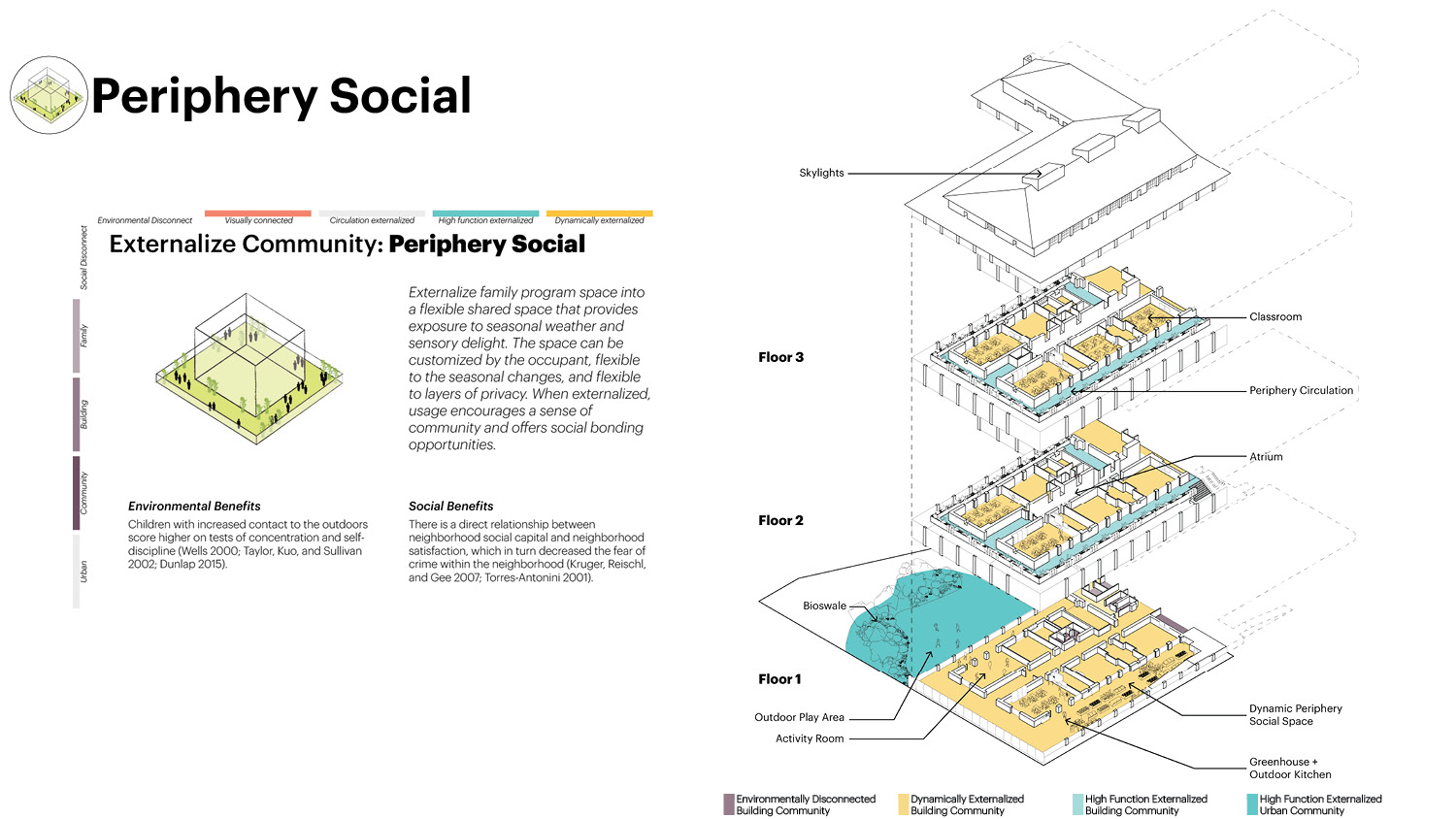

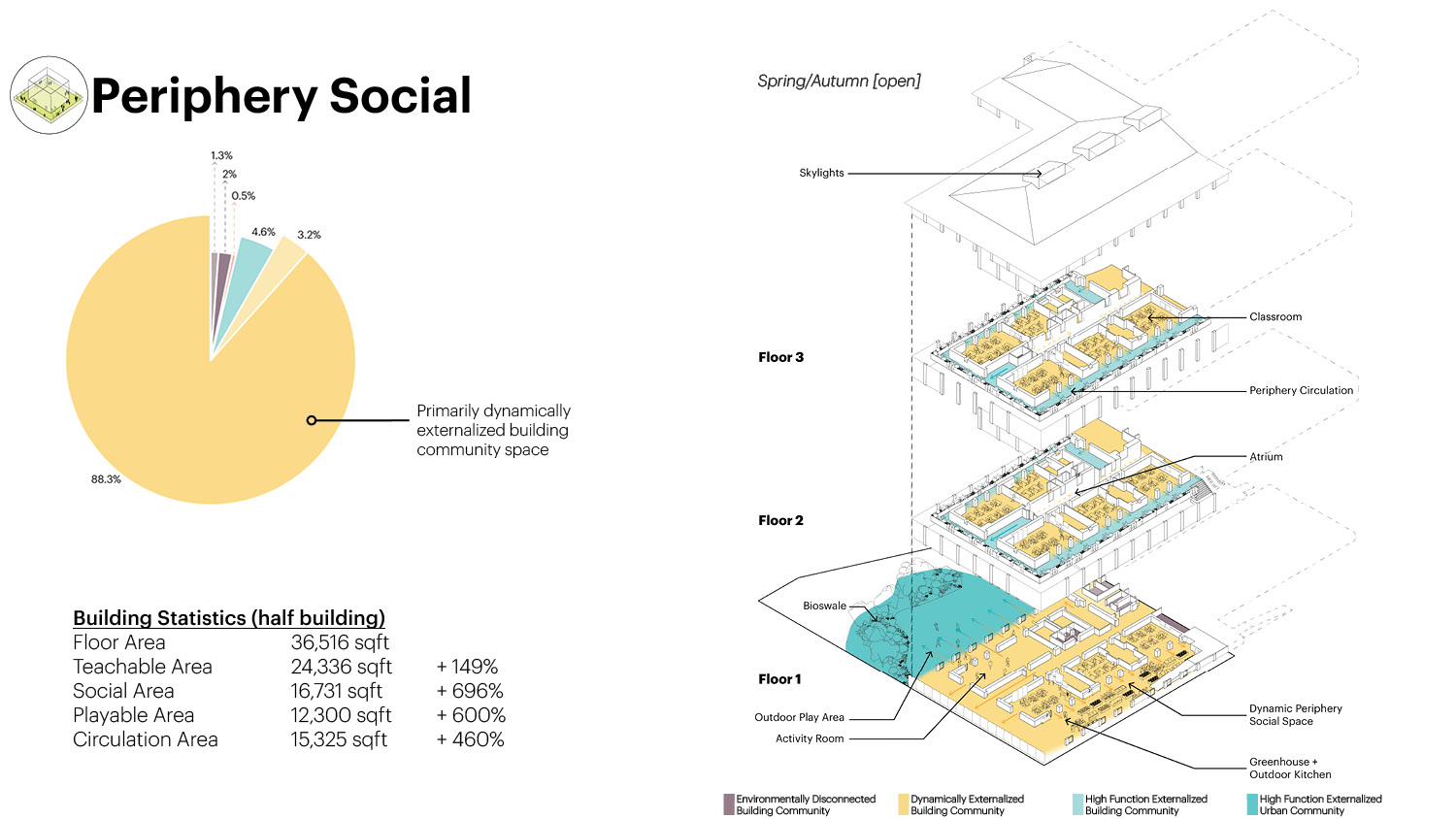

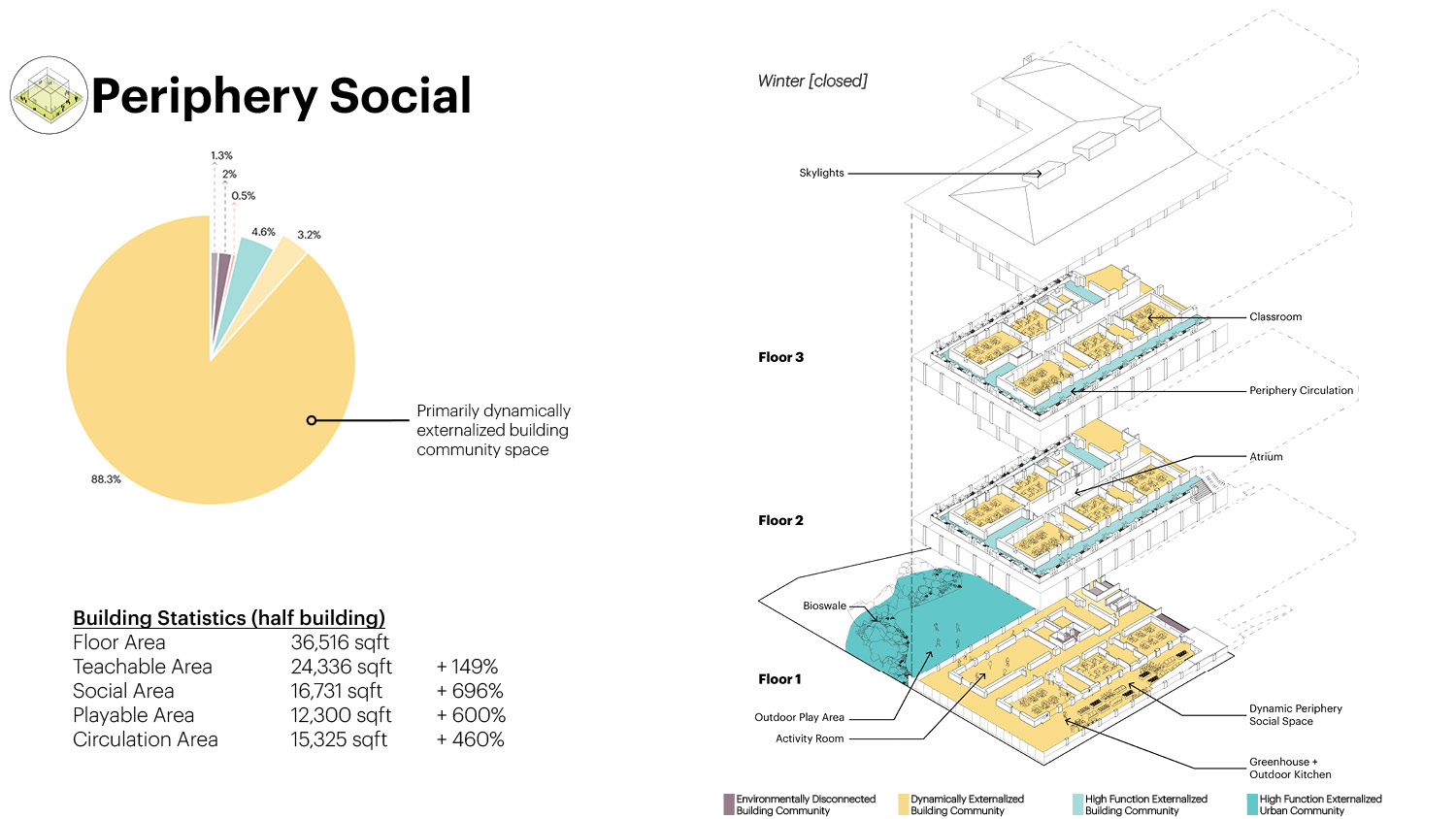

Lastly, periphery social completely transforms the school by pushing the circulation to the perimeter of the building. This hollows out the building center to create a new atrium that can allow light to penetrate in. This also provides the school flexibility to adjust the building’s porosity based on seasonal conditions.

![]()

This approach makes the building primarily dynamically externalized based on seasonal conditions, and offer more natural daylight into the whole building.

This approach makes the building primarily dynamically externalized based on seasonal conditions, and offer more natural daylight into the whole building.

Experientially, this also differs greatly from previous approaches while still being highly externalized, though it is predominantly dynamic externalization.

![]()

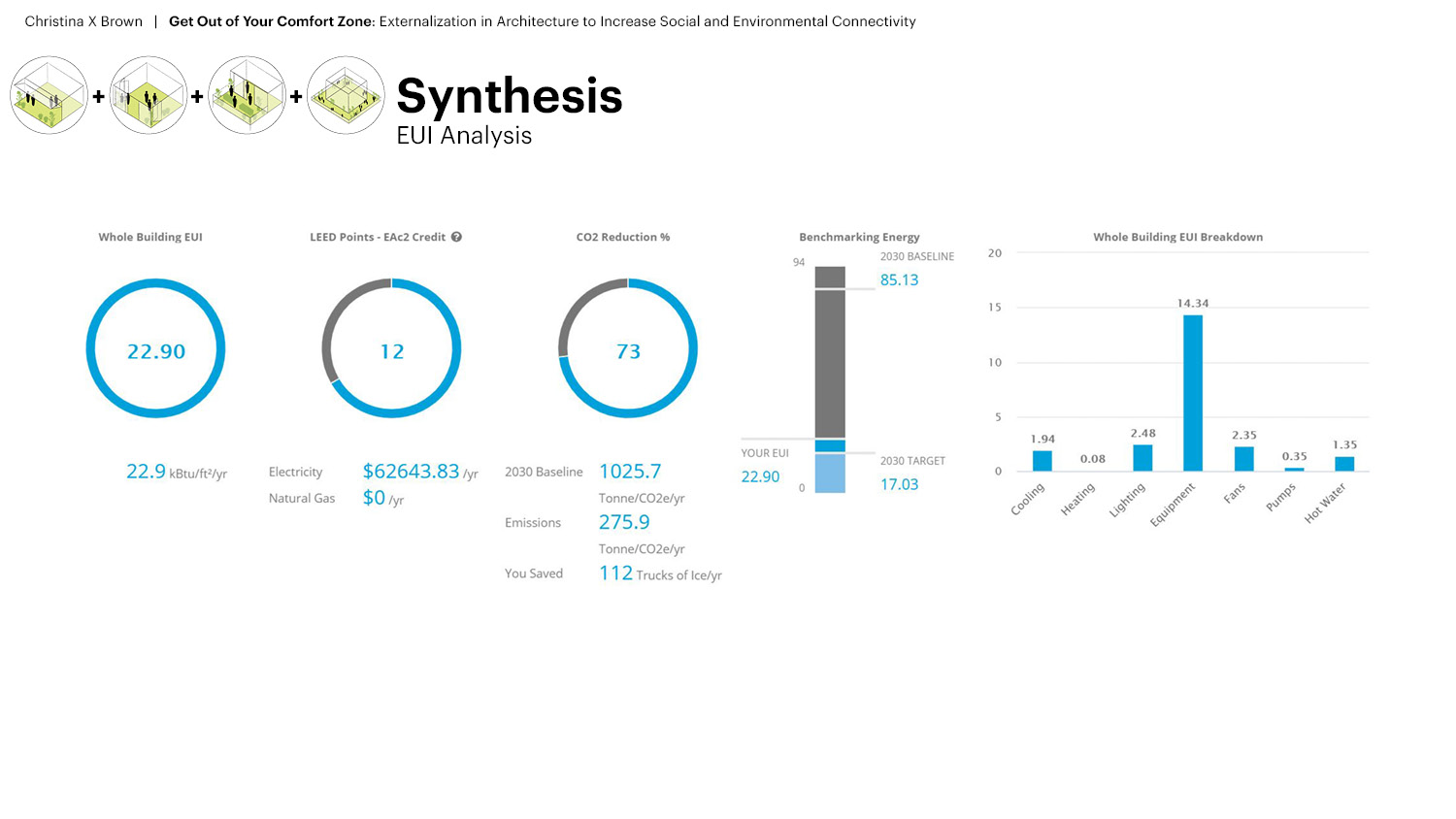

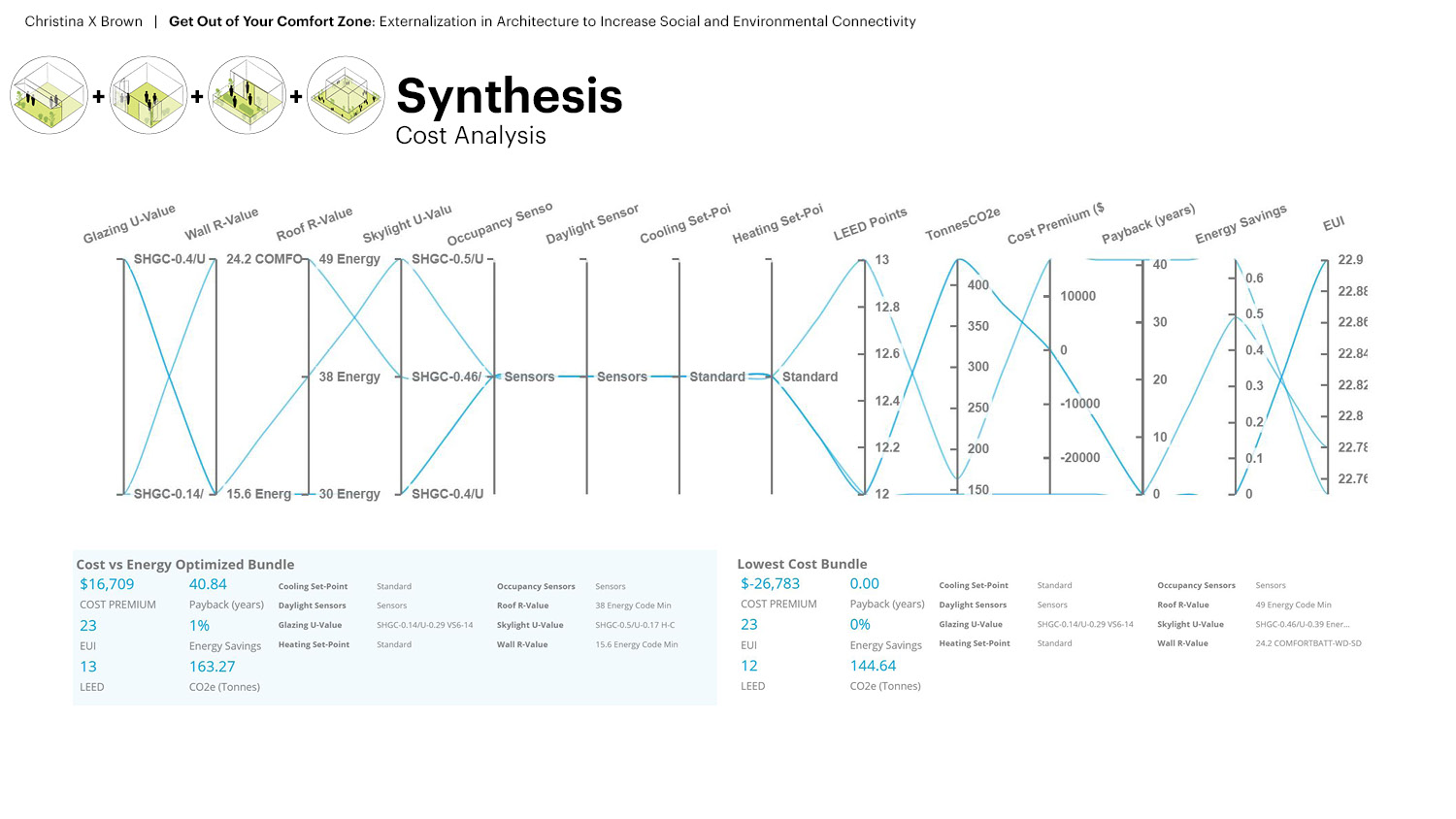

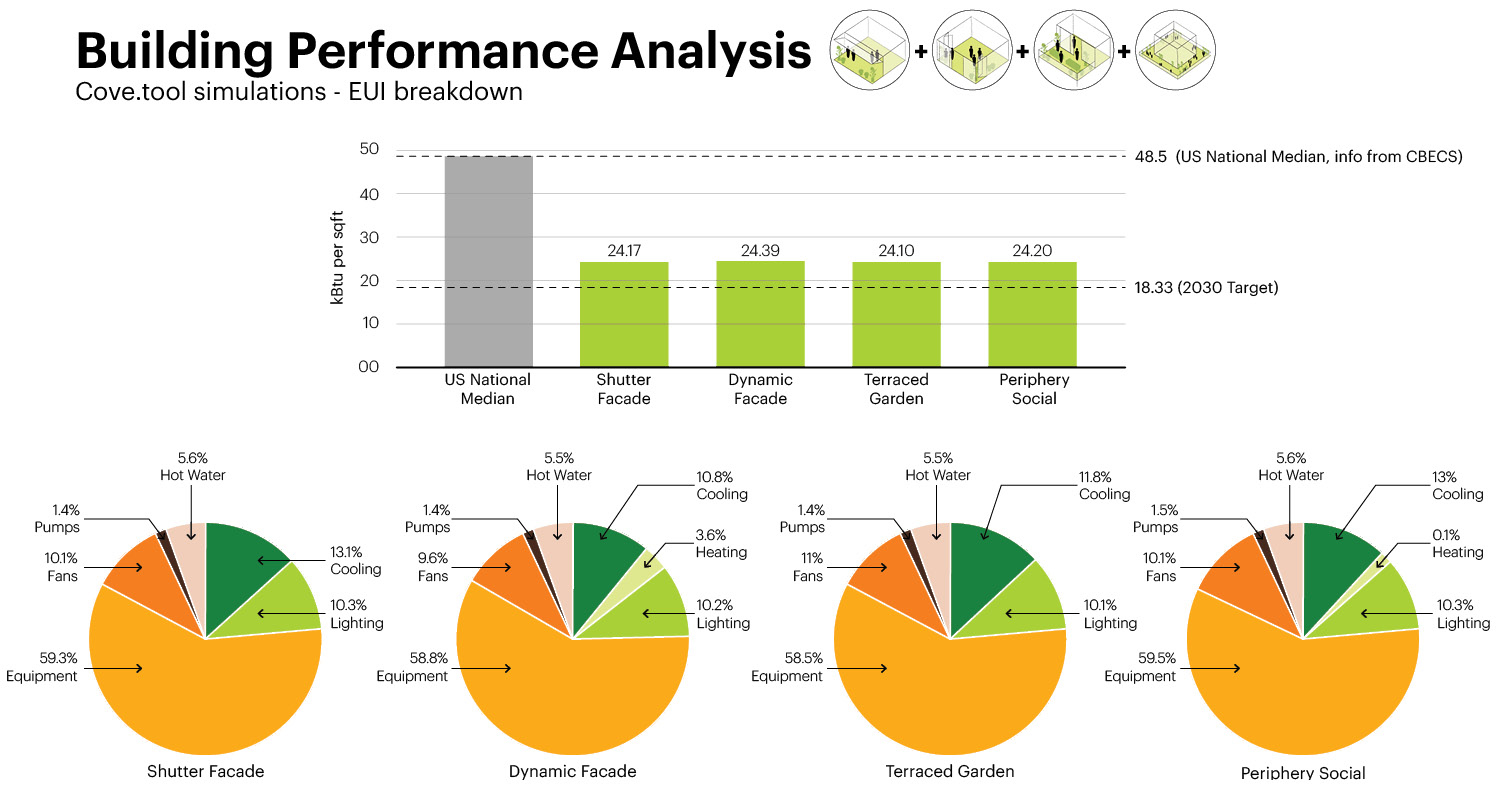

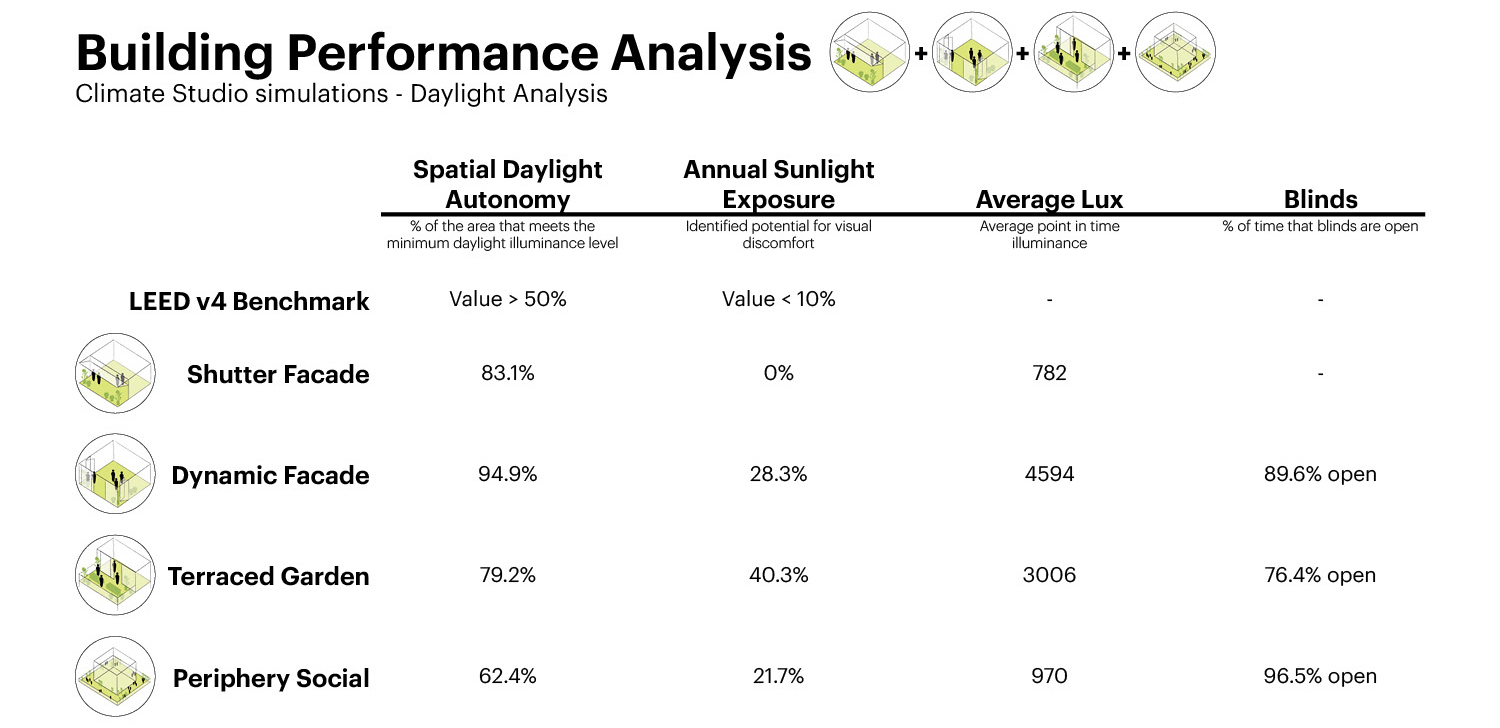

Performatively, each iteration is also half of the US national median EUI for schools through externalization, which equipment now becoming the main energy load factor in each iteration.

Additionally daylight analysis shows that the daylight quality improves greatly through these designs due to increased connections to the environment.

So what worked well in each iteration?

Each iteration does have both benefits and flaws, though it showed significant value even as a starting point using the 4 externalized strategies separately.

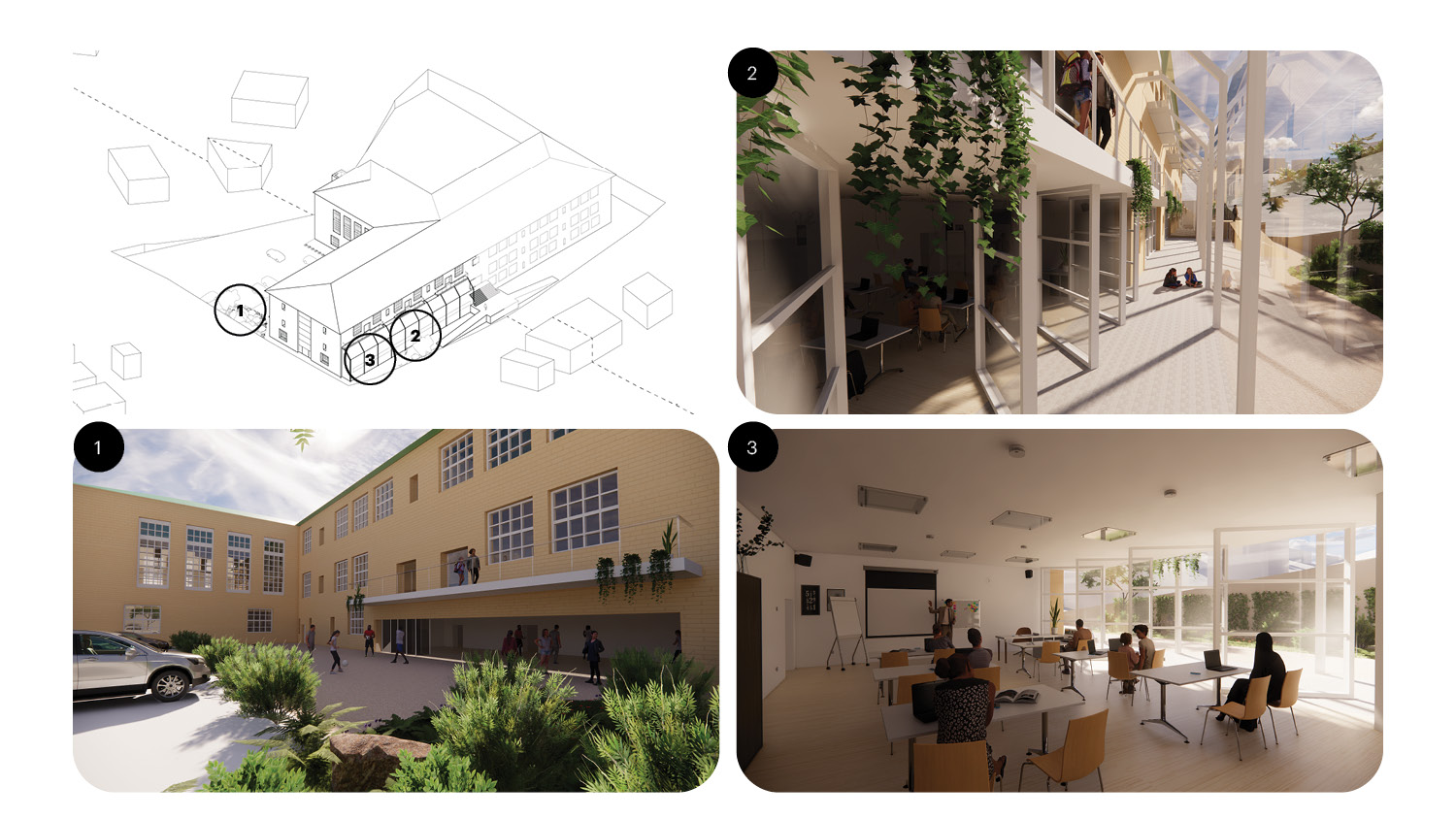

When these ideas are combined together to reflect a more externalized design approach, the school transforms even further from the original baseline. Where a classroom experience can now be porous, open, responsive; where the hallways can now be externalized as well with light penetration down to the ground floor; and where outdoor play areas can now become like these that allow for the classroom and activity room to spill out, better aligning with the school’s “out-the-door” learning approach.

And lastly, it can adapt over time, making the architecture more connective, flexible, and dynamic.

This synthesis establishes foundational research, framework, and design work to encourage and support design professionals in shifting from the current internalized design approach to an externalized approach that allows its occupants to embrace both nature and the community, so that we can create spatial environments that embraces connectivity rather than isolation.

Thank you for reading.

More detailed simulation work from the design iterations are shown below.